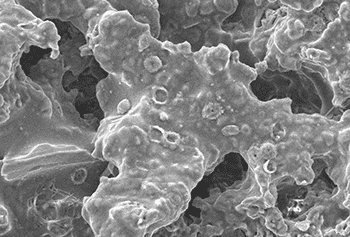

Bacterial biofilms occur all throughout nature, being a great strategy for bacteria to form a strong colony without having to be everywhere at once, and without being washed away or killed easily.

The biofilm jellanalogy

Imagine a jelly/jello cup with small pieces of fruit in it – raspberries, blueberries. The jelly/jello (the dessert, not jam you put on bread!) is the biofilm, while the fruit scattered within it is the bacteria, yeast and viruses that hide in biofilms.

If you pour liquid cream on the top of the jelly/jello, it doesn’t penetrate but sits on top. This is what your treatments are doing – sitting on top of the biofilm, not getting to the bugs where they are required. That’s one reason that treatments repeatedly fail. Biofilms also create a barrier to other microbes.

Recurrent bacterial vaginosis (BV)1, vaginal dysbiosis, urinary tract infections and yeast infections can become recurrent when one or more bacteria have made a biofilm on vaginal cells, creating an impenetrable layer that most treatments, like antibiotics, cannot penetrate.

Treatments kill the planktonic, free-floating bacteria, but do not touch the colony of bacteria hidden underneath the biofilm.

Why biofilms exist

A bacterial biofilm may occur in a wound, preventing healing, and can grow around medical implants and catheters, forming thick layers that stick closely to surfaces. Dental plaque is a biofilm, which is why it can get scraped off – and always grows back (the bacteria in your mouth don’t change that much).

The biofilm is a living shield of bacteria and protein matrix stuck to the vaginal walls, keeping other bacteria as easily-managed planktonic bacteria – good or bad, it doesn’t matter. Healthy species also make biofilms – biofilms aren’t bad in and of themselves. They also keep healthy colonies in place.

All bacteria work by producing substances that are destructive to other competitive bacteria (bacteriocins, biofilms) and by binding to the vaginal cells, providing a physical barrier to competitive bacteria. Biofilms are one such tool.

Vaginal biofilms and chronic infections

The bacterial biofilm is by its very nature resistant – but not completely immune – to the hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid produced by healthy vaginal lactobacilli. If the vagina is dysbiotic (wrong bugs in the wrong place), such as in BV, AV, yeast infections and UTIs, healthy lactobacilli species may be shut out.

Frustratingly biofilms are also resistant to even high doses of antibiotics. Hydrogen peroxide, apple cider vinegar, boric acid, antibiotic creams, gels and pastes, and whatever else you have been sticking up your vagina so far aren’t able to successfully treat chronic infections. These treatments cannot break down the biofilm.

Why don’t antibiotics work on the biofilm?

Antibiotics do not degrade biofilms; they simply put a couple of bullet holes in it, so when you stop taking antibiotics, the problem returns as if nothing happened. The biofilm is a protective living cocoon, an ingenious evolutionary survival trick.

Tackling biofilms as part of treatment for any type of dysbiosis can be of great importance for successful treatment. See Killing BV for options.

References

- 1.Verstraelen H, Swidsinski A. The biofilm in bacterial vaginosis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. Published online February 2019:38-42. doi:10.1097/qco.0000000000000516