Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the overgrowth of disruptive bacteria in the vagina, which can result in odour, unusual discharge and a shift in vaginal pH. BV may be asymptomatic, only found during health testing for other reasons.

A premenopausal healthy vaginal microbiome tends to be made up largely of protective bacteria such as lactobacilli, a lactic-acid-producing bacteria that fight pathogens and keep infections away.

If you’ve been diagnosed with BV, sadly, you’re not alone!

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) says BV is the most common vaginal issue in ages 15-44 – a whopping 30% get BV each year.

When lactobacilli dominance is disrupted, the vaginal pH can rise, allowing other types of bacteria to grow and cause an imbalance (known in medicine as vaginal dysbiosis).

This vaginal bacterial imbalance can contribute to symptoms like vaginal odour, irritation, itching, burning and unusual vaginal discharge. But, up to 84% of those with a BV diagnosis won’t get any symptoms.

Symptoms of bacterial vaginosis (BV)

- Greyish, watery discharge

- Unusual discharge

- Fishy, foul, musty or ammonia vaginal odour

- Symptoms worsen during or after menstrual bleeding

- Certain BV-related bacteria may contribute to other symptoms such as itching or inflammation

- Vaginal pH above 4.5

Understanding why BV occurs

In some uncomfortable news, the CDC also says we don’t know why BV develops. Why some of us and not others?

BV is not an infection per se, but an imbalance, caused by a change in bacterial species in your vagina. There is an umbrella term for this change in species: vaginal dysbiosis. Dysbiosis means a microbial imbalance, or simply put, the wrong bugs in the wrong place.

Vaginal dysbiosis appears in many forms, including bacterial vaginosis, yeast infections and aerobic vaginitis (AV).

Why does the balance shift to BV?

Your vagina is not an isolated area; your entire body supports it. There are lots of reasons why the balance of your vaginal flora may change for the worse, including:

- Hormonal changes (periods, birth control, pregnancy, low oestrogen states such as losing one or both ovaries, perimenopause, menopause, surgery, radiation, oestrogen-blocking breast cancer drugs, chemo, post-partum)

- Food intolerances1–3 (certain food colourings, for example, are known to inhibit your immune system)

- Stress (stress hormones like cortisol block glycogen production in the vagina, starving your healthy bacteria)

- Digestive problems4,5 (people with irritable bowel, Crohn’s and other digestive problems/diseases tend to have more vaginal infections and imbalances)

- Lifestyle choices (those who drink a lot of alcohol and smoke get more BV, while recreational drugs6 and lack of good quality sleep reduce immunity7–10)

- Poor diet11–15 (if you live on burgers, chips, frozen food and pasta, you’re setting yourself up for immune deficiencies)

- Poor immunity (your immune system is critical in fighting off pathogen invaders)

- Unprotected sex (you can catch BV from a sexual partner)

- Naturally low levels of lactobacilli (certain ethnic groups inherit naturally low levels of lactobacilli from their mothers, which can result in a greater susceptibility to BV)

What is a bacterial biofilm in BV and why does it matter?

Many bacteria build biofilms. Think of it like a perspex case that covers the vaginal cells, protecting the bacteria from treatments and other bacteria (antibiotics).

If your vagina has a lot of biofilm, symptoms may disappear temporarily as the treatments kill bacteria, but there are always more hiding under the safety of the biofilm, so BV returns, whether in a day or a week or a month.

Understanding the vaginal microbiome and symptoms

Your symptoms will depend largely on what bacteria you have present. Not all BV is the same.

For example, a G. vaginalis dominant vaginal microbiome is likely to have a fishy odour, and watery, grey discharge with or without the feeling of inflammation. Add Prevotella or Ureaplasma, and you may start feeling the inflammation. All BV causes inflammation, but you may not feel it or see it.

Get a comprehensive vaginal microbiome test to find out what’s growing in your vagina. A culture isn’t enough, and a PCR test is only just passable.

How BV is diagnosed – getting the right test

Regular swabs and culture

Every country does BV diagnosis a little bit differently, but the main method is a culture. Cultures are barely useful and now outdated compared to a comprehensive vaginal microbiome test).

A lab culture is the process of taking a vaginal fluid sample, sending it to the lab, and seeing which bacteria or fungi grow over a set period of time, say 12 or 24 hours.

Vaginal culture cannot detect some BV-related bacteria, because some microbes are hard to grow in these conditions. The dominant strains of bacteria will appear, while others will be dismissed as unimportant – which isn’t always true.

Comprehensive DNA-based vaginal microbiome testing

A comprehensive vaginal microbiome test looks for microbial DNA/RNA, and can detect the genetic material from even a dead microbe.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests can only find the test’s requirements. If you don’t ask, it won’t tell. This is why the more comprehensive tests are preferable. Get a comprehensive vaginal microbiome test online, delivered to your door.

Testing vaginal pH (acidity levels)

In BV, vaginal pH may be above 4.5, indicating an abundance of non-lactobacilli species. You can, and should, regularly test your vaginal pH at home using correctly measured vaginal pH strips.

Effectively treating BV

BV can be resolved with appropriate treatment (see the Killing BV treatment guide for further support), which may be My Vagina’s natural, effective treatments, antibiotics, or a combination of treatment strategies. The best treatment for you is the treatment that works.

The most comprehensive vaginal microbiome test you can take at home, brought to you by world-leading vaginal microbiome scientists at Juno Bio.

My Vagina’s effective, natural treatments for BV

We recommend first getting a comprehensive vaginal microbiome test, and then using one of our effective non-drug non-resistance-forming BV treatments, such as Aunt Vadge’s BV Rescue.

Other effective My Vagina BV treatments include:

- Lactulose Vaginal Prebiotic to feed protective lactobacilli

- Add a vaginal V-Spot and Life-Space Women’s Microflora Probiotic oral probiotic

- Double Whammy Vaginal Pessary if you’re not sure exactly what you have

- Fluomizin (non-drug, easy vaginal tablets)

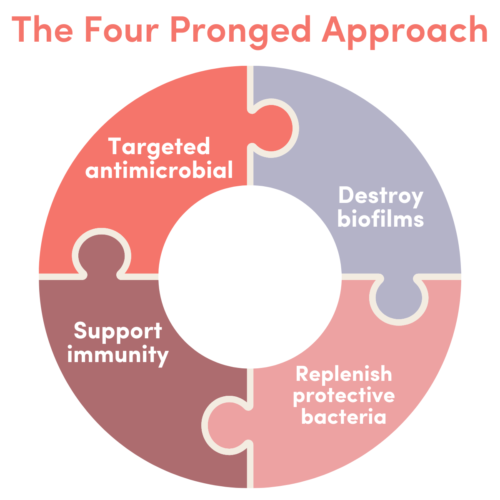

- For severe or chronic BV, use the Four-Pronged Approach Fixer Box with the antimicrobial of your choice

To restore a healthy vaginal microbiome when there is a mix of BV and AV-related bacteria, or 'mystery bad vag'.

Targeting BV and AV-related bacteria, including biofilms.

Our most extensive treatment to support the recovery of a protective vaginal microbiome, for use in prolonged or severe cases.

This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageReplenish healthy lactobacilli species the easy way - feed them their favourite food, lactulose! Comes with capsules.

Promote and support a protective vaginal microbiome with tailored probiotic species.

Specially formulated probiotic for vaginal application to promote a healthy vaginal microbiome.

Antibiotic treatment of BV

The most common medical treatment for BV is antibiotics, usually metronidazole or clindamycin. Many BV-related bacteria are antibiotic resistant, and treatment failure rates are high.

Home remedies for BV

There are plenty of at-home treatments online, which My Vagina explains the use of, such as apple cider vinegar, tea tree oil, live yoghurt, boric acid and others.

Treating chronic BV

Recurrence rates after standard medical treatment with antibiotics (usually metronidazole or clindamycin) are unacceptably high, leaving many with chronic symptoms.

If your BV won’t go away, schedule an appointment with one of My Vagina’s qualified, experienced naturopathic practitioners. Working out why BV keeps coming back over and over is important to resolve it over the long term.

Antibiotics can work well, but repeated antibiotic use has some key problems, including antibiotic resistance, damage to the overall microbiome, a poor cure rate, and feeling unwell while taking them.

My Vagina’s unique, effective Killing BV system

Here at My Vagina, we specialise in treating BV and take treatment failures seriously. We know how horrible BV is – we’ve had it too.

We also take antibiotic resistance seriously – considered a global health emergency by the World Health Organisation. Our treatments are antibiotic and hormone free, using nature-based ingredients and a holistic approach to microbial imbalances.

Understanding how and why BV develops is the key to unlocking its driving factors in your body. All BV is not created equal.

Join Killing BV and join the tens of thousands of others who have benefited greatly from the immense wealth of information and effective treatments.

Enjoy exclusive membership to the support section for plenty more information and tips and tricks. Start your drug-free journey to a healthy, happy, BV-free vagina guided by one of the world’s very best and only vulvovaginal specialist naturopaths, Jessica Lloyd.

Latest posts on BV

References16–19

- 1.Gargano D, Appanna R, Santonicola A, et al. Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns. Nutrients. Published online May 13, 2021:1638. doi:10.3390/nu13051638

- 2.Yu W, Freeland DMH, Nadeau KC. Food allergy: immune mechanisms, diagnosis and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. Published online October 31, 2016:751-765. doi:10.1038/nri.2016.111

- 3.Satitsuksanoa P, Jansen K, Głobińska A, van de Veen W, Akdis M. Regulatory Immune Mechanisms in Tolerance to Food Allergy. Front Immunol. Published online December 12, 2018. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02939

- 4.Hill JE, Peña-Sánchez JN, Fernando C, Freitas AC, Withana Gamage N, Fowler S. Composition and Stability of the Vaginal Microbiota of Pregnant Women With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Published online December 17, 2021:905-911. doi:10.1093/ibd/izab314

- 5.Schilling J, Loening-Baucke V, Dörffel Y. Increased Gardnerella vaginalis urogenital biofilm in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. Published online June 2014:543-549. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.11.015

- 6.Friedman H, Pross S, Klein TW. Addictive drugs and their relationship with infectious diseases. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology. Published online August 2006:330-342. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695x.2006.00097.x

- 7.Faraut B, Cordina-Duverger E, Aristizabal G, et al. Immune disruptions and night shift work in hospital healthcare professionals: The intricate effects of social jet-lag and sleep debt. Front Immunol. Published online September 9, 2022. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.939829

- 8.Loef B, Nanlohy NM, Jacobi RHJ, et al. Immunological effects of shift work in healthcare workers. Sci Rep. Published online December 3, 2019. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54816-5

- 9.Almeida CMO de, Malheiro A. Sleep, immunity and shift workers: A review. Sleep Science. Published online July 2016:164-168. doi:10.1016/j.slsci.2016.10.007

- 10.Thorkildsen MS, Gustad LT, Damås JK. The Effects of Shift Work on the Immune System: A Narrative Review. Sleep Sci. Published online September 2023:e368-e374. doi:10.1055/s-0043-1772810

- 11.Noormohammadi M, Eslamian G, Kazemi SN, Rashidkhani B. Association between dietary patterns and bacterial vaginosis: a case–control study. Sci Rep. Published online July 16, 2022. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-16505-8

- 12.Tuddenham S, Ghanem KG, Caulfield LE, et al. Associations between dietary micronutrient intake and molecular-Bacterial Vaginosis. Reprod Health. Published online October 22, 2019. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0814-6

- 13.Thoma ME, Klebanoff MA, Rovner AJ, et al. Bacterial Vaginosis Is Associated with Variation in Dietary Indices,. The Journal of Nutrition. Published online September 2011:1698-1704. doi:10.3945/jn.111.140541

- 14.Neggers YH, Nansel TR, Andrews WW, et al. Dietary Intake of Selected Nutrients Affects Bacterial Vaginosis in Women , ,3. The Journal of Nutrition. Published online September 2007:2128-2133. doi:10.1093/jn/137.9.2128

- 15.Noormohammadi M, Eslamian G, Kazemi SN, Rashidkhani B. Dietary acid load, alternative healthy eating index score, and bacterial vaginosis: is there any association? A case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. Published online October 27, 2022. doi:10.1186/s12879-022-07788-3

- 16.Cartwright CP, Pherson AJ, Harris AB, Clancey MS, Nye MB. Multicenter study establishing the clinical validity of a nucleic-acid amplification–based assay for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. Published online November 2018:173-178. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.05.022

- 17.Das A, Panda S, Singh A, Pala S. Vaginal pH: A marker for menopause. J Mid-life Health. Published online 2014:34. doi:10.4103/0976-7800.127789

- 18.Sianou A, Galyfos G, Moragianni D, Baka S. Prevalence of vaginitis in different age groups among females in Greece. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Published online May 4, 2017:790-794. doi:10.1080/01443615.2017.1308322

- 19.Morris M, Nicoll A, Simms I, Wilson J, Catchpole M. Bacterial vaginosis: a public health review. BJOG: An Internal Journal of Obs Gyn. Published online May 2001:439-450. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00124.x