Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is an intestinal condition whereby bacteria that normally live in the large intestine overgrow in the small intestine, or bacteria that usually live in the small intestine become too numerous1.

SIBO is the end result when one or more of several different digestive protective mechanisms fail.

Many people trying to tackle chronic vaginal infections will have digestive problems, including in some cases, SIBO.

SIBO does not directly cause vaginal problems, but it is a form of dysbiosis (wrong bugs in the wrong place) that can have serious flow-on effects to other areas of the body, including the vagina, vulva and urinary tract. Additionally, the same drivers of SIBO can also contribute to vaginal symptoms.

A quick glance at the usual suspects’ bug list shows a lot of crossovers with aerobic vaginitis (AV) and sometimes bacterial vaginosis (BV).

For the best chance of success, first confirm the diagnosis, then treat SIBO under the care of a knowledgeable practitioner.

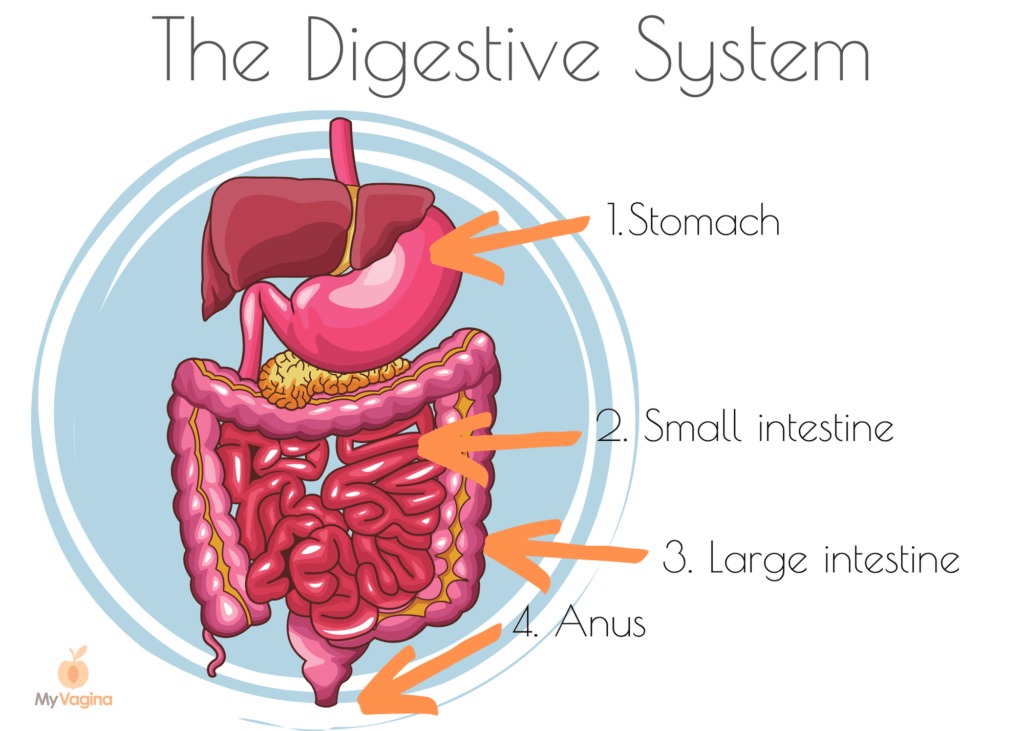

FYI, the small intestine comes before the large intestine in the digestive tract.

When farm animals rush the library

Let’s imagine for a moment that your small intestine is a quiet, orderly library with a whispers-only policy. The large intestine is a farmyard full of squawking, squealing farm animals.

Bacteria from the large intestine – farm animals – live a very different life compared to small intestine bugs – stern librarians and clean, obedient children, looking down on the farm animals from above.

The small intestine is designed expressly for the absorption of nutrients. What isn’t absorbed moves to the large intestine to be digested by large intestinal bacteria. The two intestines have very different jobs.

So back to the library. The well-behaved children sit down quietly amongst the bookshelves to eat their sandwiches and fruit, and when they’ve had enough, they throw their lunch scraps to the farm animals down in the large intestine.

The farm animals gobble up every morsel; everyone gets their fill, and nobody goes hungry. The system is working.

In SIBO, the farmyard animals realise someone left the gate open to the small intestine, and they can just walk on through and start feasting on the white-bread sandwiches and chocolate chip cookies that the kids get. They see they’ve been missing out on the best food all this time. Such an abundance of sugars, starches and carbohydrates! It’s paradise!

When the bugs from the large intestine are in the small intestine, they behave the same way as usual – gobbling up the goodies, trampling the flowers, with no concept of the damage they are doing.

The problems start when the gas the farm animals produce as they eat the kids’ delicious lunch starts to build up in the delicate small intestine. The animals are gorging themselves and doing huuuuuge farts. The poor small intestine isn’t used to having so much gas in it. It’s really uncomfortable.

Your small intestine is then overrun with the farm animals, but there are so many of them, it’s too late to shoo them back into the large intestine. The farm animals are now breeding, and there are more of them than ever. There’s just so much food here!

When cloned children take over the library

The second circumstance whereby SIBO can develop is when the small number of bacteria in the small intestine overgrow without any interference from the farm animals further down the intestine. The gate is closed, but there is something in the water and the kids have gone weird.

The school children clone themselves, replicating over and over until all you can see is a crowded library full of clone kids eating their lunch.

Usually, the small intestinal bacteria usually don’t produce much gas because their numbers are so low. A couple of sneaky farts here and there never hurt anyone, right? Well, once you get a library full of otherwise nice clone kids all doing sly farts, you eventually reach critical mass. The library is no longer a sanctuary.

In both circumstances, there’s been a breach. You now have SIBO.

The outcomes of these disruptions – symptoms of SIBO

Depending on which types of bacteria have overgrown, symptoms vary. Food is passed into the small intestine quickly, compared with the large intestine, which doesn’t start receiving food/food waste for at least two hours after eating.

Bacteria start feasting and farting in no time at all when you have SIBO, resulting in symptoms appearing soon after eating.

Symptoms of SIBO may include:

- Bloating within 30 minutes of eating

- Diarrhoea and/or constipation

- Gas, flatulence

- Cramps, griping pains

- Burping/belching

- Heartburn/reflux

- Nausea

- Food sensitivities

- Headaches

- Joint pain

- Fatigue

- Skin symptoms like eczema or rashes

- Asthma, respiratory symptoms

- Mood symptoms such as depression

- Cognition impairment like brain fog

- Oily stool

- Iron or B12 deficiency, especially when a regular red meat eater

- Nutrient deficiencies – vitamin D, calcium, bone diseases, diagnoses as a result of deficiency

- Weight loss

Common co-diagnoses

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) – 30-80 per cent of people with IBS have SIBO

- Skin disorders – acne, rosacea, psoriasis, chronic hives, scleroderma

- Food sensitivities

- Mood disorders such as depression, anxiety, insomnia

- Parkinson’s disease

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (connected with immune complexes, inflammatory cells and dietary histamines)

- Malabsorption diseases such as coeliac disease, lactose intolerance, short bowel syndrome

- Diabetes and metabolic syndromes with altered gut motility, and an increase in metabolic markers like visceral fat

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) caused by lipopolysaccharides causing inflammation and thus increased coagulation

- Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, impaired transit time, inflammation and oxidative stress

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Fibromyalgia

Some clues as to the types of bacteria you have overgrown include:

- If the bacteria interfere with bile (the substance that digests fats in your food), you may not absorb fats very well and have (sometimes oily) diarrhoea.

- If the bacteria mostly enjoy feasting on carbohydrates (then turning them into short-chain fatty acids), gas may cause bloating, but without diarrhoea – the gases are absorbed back through the intestinal lining.

- Some other bacterial species, such as Klebsiella may produce toxins that damage the intestinal mucosal lining, creating impediments to the absorption of nutrients, resulting in nutrient deficiencies. 2

The cause of SIBO

How and why the farm animals got into the library or how the kids managed to clone themselves is not always a neat and tidy story, and it might not be clear which circumstance applies to you. No matter what, you need to get a SIBO breath test to confirm the diagnosis.

We have control systems in our intestines that keep microbes in check, namely stomach acid and digestive secretions. And, intestinal motility, the process of shifting food through the digestive tract constantly.

If your gut immunity is dysfunctional or you have an anatomical abnormality in the digestive tract, your chances of developing SIBO increase.

Once you have SIBO, the inflammation itself can worsen symptoms, and result in microscopic mucosal inflammation, damaging villi (the little finger-like projections that help absorb nutrients), thinning the lining, and increasing lymphocytes (immune cells). These effects can be reversed with appropriate treatment.

The role of stomach acid in preventing SIBO

When we eat, we’re swallowing loads of bacteria. Stomach acid kills most of this bacteria, limiting its entry into the small intestine.

Stomach acid is one of our first lines of defence. Some exceptions to this include acid-loving bacteria like lactobacilli, which is why you can take probiotics, and they don’t die in stomach acid. It’s also a reason there aren’t normally very many bugs in the small intestine.

If you aren’t producing enough stomach acid for some reason, bacteria may be entering the small intestine from the mouth, which can even include mouth bacteria that are swallowed with food and saliva.

Reasons for reduced stomach acid include:

- Helicobacter pylori colonisation (beware false positives using urea-based testing!3)

- Natural ageing4

- Use of H2 receptor blockers (H2RAs) or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to block stomach acid production in the treatment of acid reflux or GORD/GERD (cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine and ranitidine, omeprazole)5–7

The role of bile, enzymes and the mucosal barrier in preventing SIBO

Bile is also responsible for killing bacteria in the stomach, and a little further down, liver and pancreatic secretions (enzymes) also play a role.

The mucosal lining of the intestine (a layer of mucous) traps bacteria, preventing attachment, with the mucin in the mucous acting as an immune substance (secretory IgA). If the immune system isn’t firing on all cylinders, SIBO can be the result.

The ileocaecal valve prevents bacteria from moving from the large intestine to the small intestine. This is the ‘gate’ in our farm animal analogy. SIBO can result from more than one of these factors not functioning as designed.

The role of healthy intestinal motility in preventing SIBO

Peristalsis is the name given to the rhythmic waves of the intestine that sweep its contents to the finish line (anus). If this process isn’t working adequately, food and bacteria can linger in the small intestine, resulting in the overgrowth of bacteria.

Preventing the attachment of bacteria by keeping them in motion is important. This is where the MMC comes in to keep the forward motion.

Understanding the MMC – your new BFF

The migrating motor complex is the ‘housekeeper’ of the digestive tract, with a hormone called motilin as the driving force. MMC is run by digestive hormones (motilin and serotonin) and the nervous system (vagus nerve and enteric nervous system). MMC is thought to be the main reason we aren’t all running around with SIBO.

Food and waste are moved through the digestive tract via a complex, tightly-coordinated series of events. Between meals, the migrating motor complex (MMC) kicks off every 90-120 minutes, sweeping digestive junk through the digestive tract towards the anus to be expelled. It keeps things moving.

The MMC moves debris out of the small intestine and into the large, preventing backflow. When the MMC system isn’t working effectively, this can set a person up for SIBO, with several conditions known to lead to poor gastric motility.

The MMC has three phases – I, II and III. Phase I is inactive, with no contractions; Phase II is intermittent, irregular, low-power contractions; and Phase III is clustered, regular high-powered contractions. If Phase III is dysfunctional, digestive contents may be retained longer than is ideal, resulting in bacterial overgrowth.

The SIBO breath test

For your SIBO test, you will be asked to drink a mixture of glucose and water; then, you will blow into a vessel every 20 minutes for three hours. The breath is then analysed for hydrogen or methane gas.

Normally there is very little hydrogen or methane in your breath, but when you have SIBO, the sugars move directly into your small intestine from your stomach, and the farm animals or school children start to feast immediately, producing farts quickly. The farts are hydrogen or methane. 8

The hydrogen or methane is absorbed through the delicate small intestinal membrane into your bloodstream and then expelled via the lungs, which is how it ends up in your breath.

Tricky, huh!

Further testing might be required depending on your circumstances.

Preparing for the SIBO test

A special diet may need to be followed to prepare for the test, especially if constipation is severe. Avoid antibiotics for two weeks before the test, do not take proton pump inhibitors a week before the test if symptoms allow, no probiotics for a week and no digestive enzymes or bitters the day before and the day of testing.

Diagnosis of SIBO

- A positive diagnosis is when there is a rise over baseline in hydrogen production of 20ppm or more within 120 minutes after ingestion of the test sugar, or

- A rise in baseline methane production of 12ppm or greater within 120 minutes after taking test sugar, or

- A rise over baseline in the sum of hydrogen and methane production of 15ppm or more within 120 minutes after taking test sugar

- Modest levels of methane gas at any level equal to or greater than 2ppm at any sample on a three-hour lactulose breath test may be a causative factor of methane-inducted constipation

- Increased methane usually means increased transit time

The impact on your intestine – the ‘why’ of symptoms

Methane:

- Slows transit time (mouth to anus) resulting in constipation

- Causes small intestine contents to flow backwards causing burps right after eating

Anaerobic bacteria:

- Consume vitamin B12 and iron, causing deficiency and microvilli malformation

- Vitamin B12 deficiency may contribute to diarrhoea

Bile salts and bile acids:

- Deconjugation of bile acids by bacteria results in poor absorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins (E, A, D) – bile is responsible for digesting fats

- Deconjugation of bile salts may cause diarrhoea

Protein:

- Bacteria use proteins from the intestinal lumen which can result in protein deficiency and excessive production of ammonia

- Malabsorption of peptides (two or more amino acids in a chain) can result in food allergies

Small intestinal permeability:

- Permeability increases in SIBO allowing larger molecules to pass through to the bloodstream than should be allowed, which can result in leaky gut and an immune reaction.

Bacterial products and metabolites:

- Toxins produced by bacteria can damage the intestine directly, known as enterotoxins

- Lipopolysaccharides (a fat molecule with a sugar molecule) from gram-negative bacteria can affect gut motility

- Metabolites from bacteria may impact motility and the enteric (gut) nervous system

- Bacteria produce many toxic compounds such as ammonia, peptidoglycans, D-lactate and serum Amyloid A, which encourage inflammation and can damage the brush border, resulting in intestinal permeability and greater body-wise effects

Inflammation:

- The small intestinal mucosa becomes inflamed (low-grade inflammation) after the immune element of the small intestinal mucosa is activated

Deficiency of carb-digesting enzymes:

- A secondary deficiency of disaccharidases (enzymes that break down sugars, i.e. lactase breaks down lactose) results in a lack of absorption of specific carbohydrates such as lactulose, sucrose and sorbitol.

- Carbohydrates ferment and result in short-chain fatty acids, which overall are useful in normal digestion, but in this situation ultimately block nutrient absorption and jejunal motility, acting as an ileal brake.

Risk factors for SIBO

- Endometriosis

- Previous pelvic or abdominal surgery (i.e. hysterectomy)9

- Medications or drugs, including narcotics

- Radiation therapy

- Underlying conditions, i.e. Crohn’s disease, diabetes

- Structural abnormalities of the digestive tract

- Ileocecal valve abnormalities, i.e. surgical resection of the valve10

- Low stomach acid (including due to use of proton pump inhibitors)11

- Ageing

- Immunodeficiency (HIV, AIDS, immunodeficiency, IgA deficiency)

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Liver cirrhosis

- Hypothyroidism (altered motility)12

- Moderate alcohol consumption13

- Scleroderma

Treating SIBO

Treatment for SIBO depends on which sort of practitioner you see. Medical doctors are more likely to prescribe antibiotics14 (usually rifaximin and neomycin); however, a functional medicine doctor, naturopath or herbalist may use a combination of diet, nutrients, supplements and herbal medicine. Lifestyle modifications may also be suggested.

Herbal medicines are as effective as antibiotics (rifaximin)15 though herbs must be used longer.

The underlying cause of this disruption to normal flora needs to be addressed or the problem may simply return after treatment. A SIBO diagnosis may be simply a sign of another underlying issue, so be cautious of treating SIBO simply as a ‘disease to be cured’. It may merely be a symptom.

Treating SIBO is likely to take several months and be a multi-step process. Reducing bacteria counts in the small intestine is a major first step, achieved by reducing the food sources for the bacteria and killing them off. Killing can be done using strong herbal medicines and/or antibiotics.

Special diets are recommended while undergoing SIBO treatment, all of which aim to reduce the sugars, starches and carbohydrates the bacteria feed on. Not all food can be used as an energy source for bacteria, so the diets limit or exclude only certain types of food.

- Low-FODMAP diet

- Biphasic diet

How small intestine and large intestine bugs are different

The small intestine typically contains gram-positive aerobes, while the large intestine contains mostly gram-negative anaerobes15.

- Aerobic: requires oxygen to survive

- Anaerobic: prefers a lack of oxygen

- Facultative: can survive both with and without oxygen

Commensal (gut) anaerobic bacteria (mostly large intestine)

- Bacteroides spp. (gram-negative)

- Lactobacillus spp. (gram-positive, facultative)

- Clostridium spp. (gram-positive)

- Fusobacterium spp. (gram-positive)

- Peptostrepotoccus spp. (gram-positive)

Commensal (gut) aerobes (mostly small intestine)

- Streptococcus spp. (gram-positive)

- Escherichia coli (gram-negative)

- Staphylococcus spp. (gram-positive)

- Enterococcus spp. (gram-positive)

- Klebsiella pneumoniae (gram-negative)

- Proteus mirabilis (gram-negative)

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa (gram-negative)

- Acinetobacter spp. (gram-negative)

- Corynebacterium spp. (gram-positive)

- Neisseria spp. (gram-negative)

- Citrobacter spp. (gram-negative)

- Micrococcus spp. (gram-positive)

How much bacteria should there be in the small intestine?

Normally bacteria is found at low levels in the small intestine, below or equal to 10³ in aspirations. Above this amount is considered indicative of SIBO.

Small intestinal fungal overgrowth (SIFO)

SIFO is characterised by excessive fungus, often Candida yeast species, in the small intestine and is associated with digestive symptoms.

In one study16 of 150 people with unexplained digestive systems:

- 40% had SIBO

- 26% had SIFO

- 34% had SIFO and SIBO

References

- 1.Sachdev AH, Pimentel M. Gastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth: pathogenesis and clinical significance. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. Published online July 16, 2013:223-231. doi:10.1177/2040622313496126

- 2.Dukowicz A, Lacy B, Levine G. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a comprehensive review. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3(2):112-122. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21960820

- 3.Brandi G, Biavati B, Calabrese C, et al. Urease-Positive Bacteria Other thanHelicobacter pyloriin Human Gastric Juice and Mucosa. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. Published online August 2006:1756-1761. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00698.x

- 4.Husebye E, Skar V, Hoverstad T, Melby K. Fasting hypochlorhydria with gram positive gastric flora is highly prevalent in healthy old people. Gut. Published online October 1, 1992:1331-1337. doi:10.1136/gut.33.10.1331

- 5.Shindo K, Fukumura M. Effect of H2-receptor antagonists on bile acid metabolism. J Investig Med. 1995;43(2):170-177. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7735920

- 6.Thorens J, Froehlich F, Schwizer W, et al. Bacterial overgrowth during treatment with omeprazole compared with cimetidine: a prospective randomised double blind study. Gut. Published online July 1, 1996:54-59. doi:10.1136/gut.39.1.54

- 7.LEWIS SJ, FRANCO S, YOUNG G, O’KEEFE SJD. Altered bowel function and duodenal bacterial overgrowth in patients treated with omeprazole. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Published online August 1996:557-561. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.d01-506.x

- 8.Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterology. Published online February 2003:412-419. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07234.x

- 9.Kim DB, Paik CN, Kim YJ, et al. Positive Glucose Breath Tests in Patients with Hysterectomy, Gastrectomy, and Cholecystectomy. Gut and Liver. Published online March 15, 2017:237-242. doi:10.5009/gnl16132

- 10.Roland BC, Ciarleglio MM, Clarke JO, et al. Low Ileocecal Valve Pressure Is Significantly Associated with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). Dig Dis Sci. Published online May 3, 2014:1269-1277. doi:10.1007/s10620-014-3166-7

- 11.Lombardo L, Foti M, Ruggia O, Chiecchio A. Increased Incidence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth During Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Published online June 2010:504-508. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.022

- 12.Patil A. Link between hypothyroidism and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Indian J Endocr Metab. Published online 2014:307. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.131155

- 13.Gabbard SL, Lacy BE, Levine GM, Crowell MD. The Impact of Alcohol Consumption and Cholecystectomy on Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Dig Dis Sci. Published online December 10, 2013:638-644. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2960-y

- 14.Gasbarrini A, Lauritano EC, Gabrielli M, et al. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Diagnosis and Treatment. Dig Dis. Published online 2007:237-240. doi:10.1159/000103892

- 15.Bohm M, Siwiec RM, Wo JM. Diagnosis and Management of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Nutr Clin Pract. Published online April 24, 2013:289-299. doi:10.1177/0884533613485882

- 16.Erdogan A, Rao SSC. Small Intestinal Fungal Overgrowth. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. Published online March 19, 2015. doi:10.1007/s11894-015-0436-2

Get a fresh perspective with a qualified, experienced vulvovaginal specialist naturopath.

This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageThe most comprehensive vaginal microbiome test you can take at home, brought to you by world-leading vaginal microbiome scientists at Juno Bio.

Easy-to-use BV and AV treatment program.

Promote and support a protective vaginal microbiome with tailored probiotic species.