Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory autoimmune condition affecting mucous membranes and the skin. LP affects around one per cent of all women, with it being more common in the mouth (gingival lichen planus).

A quarter of women with gingival lichen planus will experience vulvovaginal symptoms, including keratinisation of the skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. LP symptoms can also occur in the rectum and oesophagus.

It is common for gingival and vulvar lichen planus to occur together, but the link remain undiscovered, since the dentist and the gynaecologist don’t tend to swap notes, and symptoms may seem to be completely unrelated.1

It is also common to be treated for yeast infections or vague vaginal/vulva symptoms for many years before the correct diagnosis is made.

Onset can be slow and intermittent, with lesions appearing and disappearing. Triggers must be noted.

Symptoms of lichen planus

- Skin and vulvar itching

- Burning

- Pain

- Dyspareunia (painful sex)

- Bleeding after sex

- White plaques, scarring, thickened vulvar or vaginal skin

- Thickened skin turns white when it gets wet

- Erosions and ulcers may occur

- Destruction of the vulvar and vaginal structure

- Shiny bright red skin erosions/lesions on labia minora and vestibule

- Copious yellow discharge

- Discharge may ooze, and be made up of skin cells as well as liquid

- Blockage of the vagina due to adhesions

- Infections happen more frequently or easily

- Oesophageal and gingival LP can cause difficulty swallowing or uncomfortable mouth symptoms

Why does lichen planus develop?

The cause of lichen planus is unknown, however one theory is that activated T-cells attack basal keratinocytes, considered a cell-mediated immune response.2

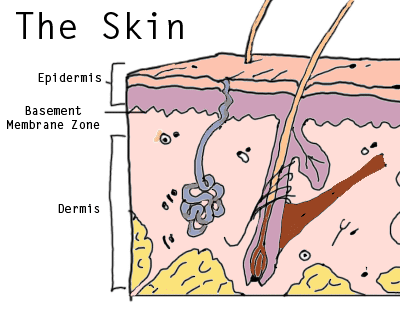

Unfortunately at this point no antigen has actually been discovered, so the label of ‘autoimmune’ isn’t 100 per cent. LP is considered a type IV hypersensitivity reaction whereby the lymphocytes (white blood cells of the lymphatic system) increase in the skin membrane and dissolve or liquefy the basement membrane zone of the epidermis, which is the bottom of the top layer of skin. (See diagram)

It occurs in women between the ages of 30 and 60 most frequently, and diagnosis is spread between clinicians: dermatologists, gynaecologists, dentists and sometimes even gastroenterologists. The most common form affecting the vulva is erosive LP.

Prevalence is high in postmenopausal women, since the impact of lowered oestrogen on skin integrity, strength and function plays a major role. 3

Vulvodynia can also be present. Vulvodynia is pain in the vulva or vestibule for no apparent reason. It could be a genetic predisposition, stress (physical and emotional), skin injury like a scratch (isomorphic response), herpes, viral infection that could modify antigen behaviour, or contact allergy.

Lichen planus can be confused with a drug reaction from beta-blockers, methyldopa, quinine, quinidine, or penicillamine.

Lichen planus has four varieties:

- Erosive LP (affects the vulva and vagina, often the labia minora and vestibule)

- Papulosquamous LP (affects the vulva, anal and perineum with small, very itchy red/purple papules, or pink lesions that are hard to find the edges of, often confused with genital warts or molluscum contagiosum)

- Hypertrophic LP (affects the perineum and perianal area, with rough lesions)4

- Vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome / pluri mucosal LP (affects the vulva, vagina and mouth)5

Treating lichen planus

These conditions are often chronic and recurrent, being resistant to treatments, and there is no standardised effective treatment for LP. Topical medication will be tried first in most cases, with systemic medicine (taken into the blood via stomach or injection) being reserved for severe cases.

- Some women get relief from fusing from using a borax solution applied daily.

- Corticosteroid ointment is the first port of call (fluocinonide 0.05% or clobetasol propionate 0.05%), used daily until lesions resolve, but no longer than three months of daily use.6 Corticosteroids lower immunity, so opportunistic pathogens can invade, such as yeasts, and so treatments can oscillate between the LP and yeast infections to keep a balance.

- Clobetasol gel injections into the vagina may be suggested, along with vaginal dilators to keep the vagina open.

- Methotrexate may also be used.

- Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are sometimes used, however they are very expensive

- Surgery may be recommended in some instances to open closures or adhesions, and allow better function and accessibility. Scarring can close the vagina entirely quite quickly.

Ointments work better than creams. Hot baths to soften lesions before applying corticosteroids has been recommended. Suppositories may be prescribed for vaginal affliction, along with vaginal dilators. Your doctor may prescribe immunosuppressant drugs.7

Negative drug reactions are not unheard of, particularly with older women on heart, thyroid or cholesterol medications. Some may not work well being substituted.

Taking photos is advised, by a physician and at home, to track the disease’s progress. Getting in early is best to avoid the vagina/vulva being completely closed, and requiring further drastic measures.

Self care at home

- Avoid any irritants – laundry liquids, perfumes, douches, soaps, lubricants, spermicides, etc.

- Seek early treatment – early intervention can mean a usable vagina and vulva.

- Find a physician who is experienced in treating this condition – it has only come to light really in the past few years, so many doctors may not even be aware of it, let alone how to treat it effectively.

- Join a lichen planus support group, find forums online, and talk to others with the condition – being understood and able to share success and failures and what other people have done that worked for them is invaluable as a source of comfort and resources.

- Get a counsellor, discuss the implications to your relationships with your partner(s), and know that it’s ok to feel sad and angry. Your diagnosis may mean you will never be able to assume the health and wellbeing of your vagina, and that you will always have to work to keep it healthy and well. If you have lost part or full function of your vagina, grieve. Try to stay sane.8

- Do a total overhaul of your diet and lifestyle. Your body is responding to an unknown, and therefore it’s critical to ensure you are giving your body everything it needs to defend itself. This means going on an anti-inflammatory diet, taking specific supplements that provide nourishment to the skin, possibly utilising herbal medicines to help with symptoms, scarring, and inflammation.

- Make an appointment with a qualified, experienced naturopath and see which areas can be improved – there are no doubt many. Target your changes to get the most benefit out of them – for example while eating more lettuce may seem like you are eating more vegetables, if you switch iceberg for spinach, you get a very hefty increase in nutrients for the same amount of food.

- 1.Sharma N, Malhotra S, Kuthial M, Chahal K. Vulvo-vaginal ano-gingival syndrome: Another variant of mucosal lichen planus. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. Published online 2017:86. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.203432

- 2.Day T, Wilkinson E, Rowan D, Scurry J. Clinicopathologic Diagnostic Criteria for Vulvar Lichen Planus. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Published online March 21, 2020:317-329. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000532

- 3.Marnach ML, Torgerson RR. Vulvovaginal Issues in Mature Women. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Published online March 2017:449-454. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.031

- 4.Day T, Weigner J, Scurry J. Classic and Hypertrophic Vulvar Lichen Planus. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Published online October 2018:387-395. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000419

- 5.Lucchese A, Dolci A, Minervini G, et al. Vulvovaginal gingival lichen planus: report of two cases and review of literature. Oral Implantol (Rome). 2016;9(2):54-60. doi:10.11138/orl/2016.9.2.054

- 6.Dunaway S, Tyler K, Kaffenberger J. Update on treatments for erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus. Int J Dermatology. Published online October 20, 2019:297-302. doi:10.1111/ijd.14692

- 7.Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Published online August 2015:140-149. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.04.001

- 8.Cheng H, Oakley A, Conaglen JV, Conaglen HM. Quality of Life and Sexual Distress in Women With Erosive Vulvovaginal Lichen Planus. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Published online April 2017:145-149. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000282