Cyclic vulvovaginitis is typically caused by a recurrent yeast infection or lactobacillus overgrowth (cytolytic vaginosis or CV), that flares up at the same stage of each menstrual cycle. Cyclic vulvovaginitis isn’t so much a condition itself, as a symptom of another condition.1

Yeast infections and lactobacillus overgrowth cause very similar symptoms (thick, white discharge, sour odour or no odour, itching, burning, soreness). Both may flare up at specific times in the menstrual cycle, but which one is it? We’ll help you find out.2

If multiple yeast treatments have yielded no results, you’d be looking towards A) a drug-resistant yeast species or B) cytolytic vaginosis.

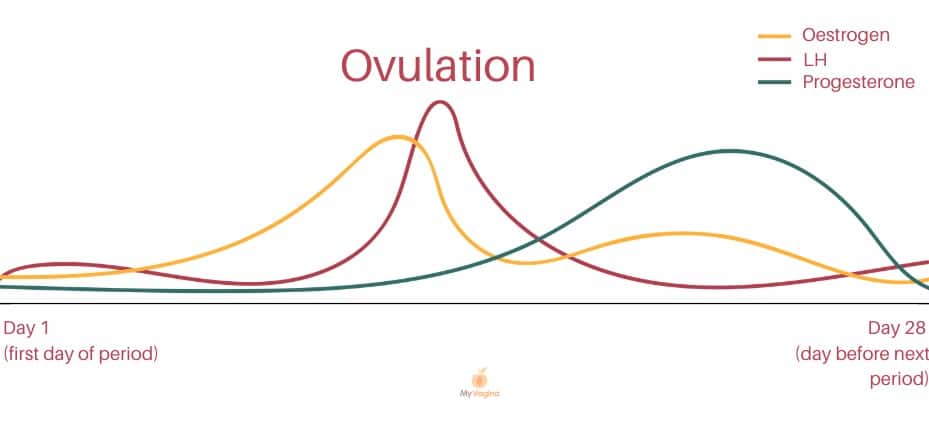

Cyclic vulvovaginitis occurs in those with an active menstrual cycle and seems to be related to fluctuating levels of oestrogen.3,4

If you are on hormonal birth control, these fluctuations will not be present or be significantly less. Being on hormonal birth control may also be a contributing factor in frequent yeast infections.

Symptoms of cyclic vulvovaginitis

- Burning

- Itching

- Stinging

- Irritation

- Aggravated by sex

- Worse the day after sex

- No symptoms between periods

- Symptoms around ovulation/in the luteal phase

- Symptoms immediately before, during or after periods

Diagnosis of cyclic vulvovaginitis

A swab will be taken to check for pathogens and healthy flora. If possible, your practitioner should examine your vaginal fluid under a microscope (a wet mount/wet prep).

The timing of symptoms is important to help determine the cause of your symptoms, with main hormonal points of interest being one or more of ovulation, the start/end of bleeding, during bleeding, and the luteal phase (from ovulation to period).5,6

Yeast

Higher oestrogen levels are associated with increased candidal (yeast) and lactobacilli activity in the vagina. Thus, zones of high oestrogen across the cycle may coincide with yeast or lactobacilli overgrowth, for example, during ovulation and up until bleeding begins (luteal phase).7

During the luteal phase (the second part of the menstrual cycle – after ovulation and before the next period) oestrogen levels result in a special sugar, glycogen, being deposited into the top layer of cells inside the vagina (the epithelium). These sugars feed lactobacilli and yeasts.

Progesterone is high in the luteal phase, causing the epithelial cells – full of sugar – to shed into the vagina, where yeast and lactobacilli have a feast.

When yeasts feed, they also multiply, resulting in symptoms. But, once bleeding arrives, all hormones shut off and the food dries up, and symptoms disappear.

There may be more severe symptoms right before bleeding starts when sugar levels are high.

During pregnancy, oestrogen levels are high, so as the vaginal cells naturally shed, more sugars are available for yeasts. Those with diabetes and impaired immunity are also more likely to get recurrent/cyclic yeast infections.8

Yeast or lactobacilli?

Both yeast and lactobacilli both show a normal vaginal pH of 3.8 – 4.5.

It’s valuable to make sure proper testing is performed to determine the best course of action. Many yeasts are drug-resistant, so having susceptibility testing and correct antifungal drugs is key to a successful treatment if it’s determined to be yeast.

Yeast treatments are topical and/or oral, however, there are multiple options for treating yeast without drugs.

Boric acid can work very well, and should potentially be tried before antifungal treatment to avoid drug resistance, but you can find more options on our yeast infections page.

If yeast is not identified, antifungal treatment should be avoided.

Some yeasts are rarer and harder to treat, so exact species should be determined prior to treatment. If yeast is not cultured, all antifungal agents should be discontinued.

Lactobacillus overgrowth (cytolytic vaginosis)

To be sure to rule out cytolytic vaginosis, an examination of the lactobacilli presence in the vagina should be conducted. Tests may include a PCR assay on species and abundance or a wet mount under a microscope in clinic.9

The clue as to whether lactobacilli are involved is the luteal phase (ovulation onwards) of symptom recurrence. Clinicians can make this diagnosis based on microscopic examination of vaginal fluids and ruling out other infections.

Management of cytolytic vaginosis centres around reducing the overgrowth of healthy flora by increasing the pH temporarily with baking soda in a sitz bath or douches. Baking soda is alkaline, whereas lactobacilli like it acidic, so baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) naturally reduces colonies.10,11

Baking soda treatment can be found on the cytolytic vaginosis page.

Other causes of cyclic vulvovaginitis

Oestrogen hypersensitivity

If a strain of yeast or an overgrowth of lactobacilli is not found, the hypersensitivity may be associated with oestrogen, if the problem arises before bleeding starts.

Another type of infection

If symptoms start after bleeding starts, it is unlikely to be oestrogen or progesterone-related, since levels drop off completely once bleeding begins. The loss of protection offered by both oestrogen and progesterone (with increased lactobacilli) may cause symptoms during bleeding, for example, odour caused by bacterial vaginosis.

Dermatitis or allergy

Cyclic vulvovaginitis could also be a type of dermatitis or allergic reaction, possibly to tampons or pads if the discomfort begins once menstrual products are being used. To reduce contact with irritants, it may be helpful to use period underwear or a menstrual cup during menstruation.

A non-soap cleanser should be used for washing. Dermatitis will be treated with hydrocortisone cream, but caution should be advised and long-term use is not recommended.

Developing vaginal or vulvar pain as a result

Cyclic vulvovaginitis can lead to vulvodynia, which is a chronic vulvar pain condition.12

A low-oxalate diet may be recommended while the cause is sought. Oxalates can build up via various mechanisms, including microbial activity, and cause the threshold to be reached after eating certain foods. Talk to your healthcare practitioner to see if this is appropriate in your circumstances.

References

- 1.Secor R. Cytolytic vaginosis: a common cause of cyclic vulvovaginitis. Nurse Pract Forum. 1992;3(3):145-148. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1472886

- 2.Eleutério J Jr, Campaner AB, de Carvalho NS. Diagnosis and treatment of infectious vaginitis: Proposal for a new algorithm. Front Med. Published online February 9, 2023. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1040072

- 3.Zhang X, Essmann M, Burt ET, Larsen B. Estrogen Effects onCandida albicans:A Potential Virulence‐Regulating Mechanism. J INFECT DIS. Published online April 2000:1441-1446. doi:10.1086/315406

- 4.Cheng G, Yeater KM, Hoyer LL. Cellular and Molecular Biology of Candida albicans Estrogen Response. Eukaryot Cell. Published online January 2006:180-191. doi:10.1128/ec.5.1.180-191.2006

- 5.Sjöberg I, Cajander S, Rylander E. Morphometric Characteristics of the Vaginal Epithelium during the Menstrual Cycle. Gynecol Obstet Invest. Published online 1988:136-144. doi:10.1159/000293685

- 6.Špaček J, Buchta V, Jílek P, Förstl M. Clinical aspects and luteal phase assessment in patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. Published online April 2007:198-202. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.03.009

- 7.Fidel PL Jr, Cutright J, Steele C. Effects of Reproductive Hormones on Experimental Vaginal Candidiasis. Kozel TR, ed. Infect Immun. Published online February 2000:651-657. doi:10.1128/iai.68.2.651-657.2000

- 8.Bagga R, Arora P. Genital Micro-Organisms in Pregnancy. Front Public Health. Published online June 16, 2020. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00225

- 9.Ventolini G, Gandhi K, Manales NJ, Garza J, Sanchez A, Martinez B. Challenging Vaginal Discharge, Lactobacillosis and Cytolytic Vaginitis. JFRH. Published online May 24, 2022. doi:10.18502/jfrh.v16i2.9477

- 10.Oerlemans EFM, Bellen G, Claes I, et al. Impact of a lactobacilli-containing gel on vulvovaginal candidosis and the vaginal microbiome. Sci Rep. Published online May 14, 2020. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-64705-x

- 11.Liu P, Lu Y, Li R, Chen X. Use of probiotic lactobacilli in the treatment of vaginal infections: In vitro and in vivo investigations. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. Published online April 3, 2023. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2023.1153894

- 12.Paavonen J. Vulvodynia ‐ a complex syndrome of vulvar pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. Published online April 1995:243-247. doi:10.3109/00016349509024442

The most comprehensive vaginal microbiome test you can take at home, brought to you by world-leading vaginal microbiome scientists at Juno Bio.

Unique, comprehensive BV, AV and 'mystery bad vag' treatment guide, one-of-a-kind system, with effective, innovative treatments.

Promote and support a protective vaginal microbiome with tailored probiotic species.