Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Table of contents

- What is cytolytic vaginosis?

- Why does cytolytic vaginosis develop?

- A temporary overgrowth of lactobacilli vs cytolytic vaginosis

- Symptoms of cytolytic vaginosis

- How do I know if I have cytolytic vaginosis?

- How cytolytic vaginosis works

- Normal functioning of lactobacilli in the vagina

- How often is cytolytic vaginosis diagnosed?

- Diagnosis of cytolytic vaginosis

- To diagnose cytolytic vaginosis, the following must be true:

- Treating cytolytic vaginosis with baking soda

- Cytolytic vaginosis FAQ

- Related Posts

- References 4–10

What is cytolytic vaginosis?

While lactobacilli are one of the most helpful microorganisms in the human vaginal tract, it isn’t always good news if these generally protective bacteria get out of control and one species dominates.

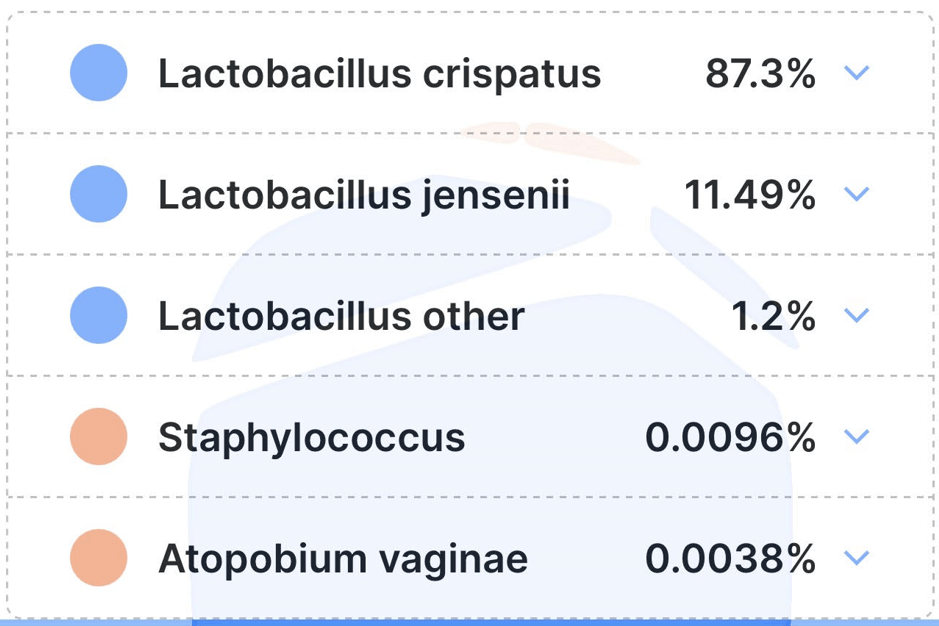

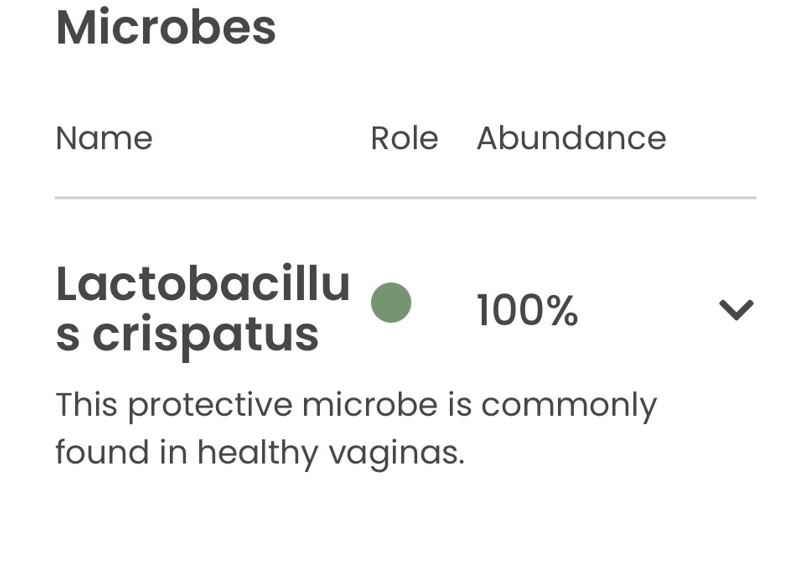

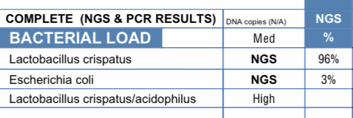

Typically, lactobacillus overgrowth syndrome, also known as cytolytic vaginosis (CV), has a high Lactobacillus crispatus count, sometimes L. gasseri or L. jensenii, and occasionally L. iners, typically 98 per cent and above on a comprehensive vaginal microbiome test.

When lactobacilli overgrow, it can look and feel like a yeast infection, but this condition won’t respond to antifungals. Cytolytic vaginosis can go on for a long time undiagnosed because all the classic markers of a problem are not apparent – it seems like a healthy vaginal microbiome.

Why does cytolytic vaginosis develop?

It’s not clear why this dominance occurs (but My Vagina specialist practitioners have a few hunches and lots of experience treating CV!).

In our clinical experience, CV often switches with aerobic vaginitis (AV), so treatment can be tricky unless you have an experienced, knowledgeable practitioner who can unpick the cause in your particular case.

We have associated CV with certain energy sources that are in abundance due to metabolic pathway disturbances, histamine and oestrogen abundance, blood sugar dysregulation, and other causes. Everyone is different, so a consultation is advisable if the CV doesn’t resolve by itself.

If you are susceptible to CV, then the use of lactulose and probiotics orally and vaginally may cause the development of or a worsening of CV or lactobacillus overgrowth symptoms. It is advisable to stop use of all probiotics and prebiotics that promote lactobacillus species if you suspect or are diagnosed with CV.

A temporary overgrowth of lactobacilli vs cytolytic vaginosis

CV is when the single lactobacillus species has completely dominated the microbiome and is causing symptoms.

Lactobacillus overgrowth is temporary and will fade away once the source has been removed (e.g. prebiotic lactulose or probiotics).

Overusing probiotics or prebiotics such as lactulose can result in a temporary overgrowth of lactobacilli, but unless you have underlying causes (excess oestrogen, diabetes, biochemical pathway interruptions, excess histamine), this doesn’t turn into CV.

CV is a diagnosis that reflects a problematic state of vaginal flora, which can be tricky to shift unless you remove the underlying driver.

Symptoms of cytolytic vaginosis

- Burning is a key symptom (due to high lactic acid)

- Itching

- Discharge usually thick and white, may be clumpy or sticky

- Irritation

- Soreness

- Painful sex (dyspareunia)

- pH 3.5-4.0, often sits around 4.0 consistently

- Cyclical increase in symptoms at ovulation due to increase in estrogen

- May correspond with estrogen hormone therapy, particularly postmenopause

- Symptoms clear during menstrual bleeding (higher pH, lower estrogen)

- May mimic a yeast infection, but yeast treatments don’t work

Example: HEALTHY VAGINAL MICROBIOME – NOT CV

Example: CV VAGINAL MICROBIOME

Example: SUSPICIOUS CV-AV-ISH VAGINAL MICROBIOME

How do I know if I have cytolytic vaginosis?

The best way to determine if you have CV is to get a comprehensive microbiome test, and talk to an experienced practitioner at My Vagina about your results. Your symptoms and test results will help determine if you have CV, but importantly, your practitioner can help work out why and provide effective treatment.

A doctor with a microscope, who is experienced in vaginal wet mounts and understands how to identify CV, will be able to diagnose CV based on their observation under the microscope and your clinical symptoms.

CV does not occur in healthy vaginas, but someone may have high lactobacilli counts and not have any symptoms, in which case there is nothing to worry about.

When a suspected (untested) yeast infection doesn’t respond to antifungals, over and over, and when probiotic use worsens the problem, you may suspect CV.

Cytolytic vaginosis tends to be cyclic, as the energy supply relies heavily on oestrogen to stimulate sugars used as an energy source. This means symptoms will get worse at certain times of the menstrual cycle when oestrogen is high, for example, ovulation.

If you are on hormonal contraceptives, oestrogen levels tend to stay stable, so you may experience symptoms less cyclically, but they will drop off during your period.

How cytolytic vaginosis works

Cytolytic vaginosis is also called lactobacillus overgrowth syndrome or Doderlein’s cytolysis, and is characterised by an overgrowth of lactobacilli species. This overgrowth causes damage to vaginal cells.

cyto means cell

lytic means death

cytolytic vaginosis is, therefore a condition involving the disintegration of the vaginal cell wall

Normal functioning of lactobacilli in the vagina

A healthy vagina has an abundance of lactobacilli species that work to ward off invaders like E. coli, Candida albicans and glabrata, and various other species like Gardnerella vaginalis. Lactobacilli produce hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid, among other bacteriocins, in their normal daily war against all things not vagina, including HIV.

Lactobacilli do a great job, using glucose as a food source, taken from the vaginal wall and provided largely by the action of oestrogen.

In a normal vagina, the presence of low numbers of lactobacilli has been shown to have a protective effect against yeast infections by blocking the adhesion of the yeasts to the vaginal walls as they compete for nutrients.

Some women in their fertile years, however, may develop an overgrowth of lactobacilli, which alone (or sometimes with other bacteria) can cause damage to the vaginal walls that results in the cells dying. This causes vaginal discharge.

This discharge is then misdiagnosed as a yeast infection and antifungals are prescribed. Women with diabetes (any kind) may have an overabundance of glycogen (vaginal glucose) due to blood sugar dysregulation, which feeds the lactobacilli and allows their overgrowth.

Symptoms may also increase during ovulation, when oestrogen spikes, causing more glycogen to be available as energy for lactobacilli.

How often is cytolytic vaginosis diagnosed?

While it isn’t usually the primary focus of a doctor’s visit, there are some stats available. In one study (Cerikeioglu et al 20041), 210 women with vaginal discharge and other symptoms that looked like a yeast infection were examined, and 15 of them were found to have cytolytic vaginosis.

Another study (Wathne et al 19942) found around five in 101 women had cytolytic vaginosis.

It is estimated that while yeast infections comprise up to 30 per cent of all gynaecological complaints associated with discharge, CV makes up between five and seven per cent of those in the same patient population. It is considered a significant clinical condition.

Diagnosis of cytolytic vaginosis

A yeast infection and BV must be excluded by further investigations. This is done by testing the following:

- Normal pH is found in cytolytic vaginosis (3.5-4.5)

- Leukocytes (white blood cells involved in immune responses) are not observed in cytolytic vaginosis, whereas they are in yeast infections

- Typical yeast cells are not found

- Bacterial vaginosis is excluded by pH tests and the whiff test (BV presents with an alkaline vagina, more than 4.5)

- Negative culture results in sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) (for testing for certain fungi)

To diagnose cytolytic vaginosis, the following must be true:

- Increased lactobacilli numbers

- No Trichomonas, Gardnerella or Candida on a wet mount

- Few white blood cells

- High suspicion

- Discharge

- pH between 3.5 and 4.5

Treating cytolytic vaginosis with baking soda

Reducing lactobacilli numbers can be done by elevating the vaginal pH using a sodium bicarbonate douching solution or suppository. This treatment should help to restore the natural balance after three weeks; however, if symptoms worsen, stay the same or become different, cease treatment and seek re-evaluation.

Cytolytic vaginosis douche bicarb treatment mixture

- 1-2 tablespoons of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate)

- 4 cups of warm water

Douche twice-weekly for one week on, one week off, for three weeks.

Cytolytic vaginosis suppository bicarb treatment mixture

- Vagina-safe empty vegetable capsules (not gelatin), size 0 or 1 is fine

- Fill with baking soda

Insert one capsule deep into the vagina twice a week for one week on, one week off, for three weeks.

When should I see results from the bicarb cytolytic vaginosis treatment?

Each of you will be a bit different, but the treatment period is over several weeks, and therefore, the results will also be over several weeks – but you should feel some relief immediately.

Don’t overdo this treatment, as you don’t want to go in the other pH direction too far and leave your vagina open to other pathogens. Avoid probiotics and milk kefir (anything containing lactobacilli) for your treatment time, and make sure you evaluate why this has been allowed to occur.

If you are not sure, seek the help of a qualified, experienced healthcare provider who is knowledgeable about the vaginal microbiome.

What do I do if I don’t respond to the bicarb cytolytic vaginosis treatment?

Testing and treatments are haphazard at best, with this condition not even necessarily acknowledged by many doctors3. Researchers are still learning about it, and therefore many doctors are unaware of how to test for or treat lactobacillus overgrowth. We spend so much time trying to get these protective bacteria to proliferate and make themselves at home that it is somewhat counterintuitive to now see them as the enemy.

We suggest you see a practitioner who either knows about CV or is willing to learn and who wants to help you.

A naturopath, herbalist, acupuncturist, or nutritionist may be able to shed some light on what they think is happening since this is – in My Vagina’s experience – not a vagina problem but a systemic problem. Once the underlying issue is resolved, the vaginal microflora will diversify, and symptoms will disappear.

Cytolytic vaginosis FAQ

Cytolytic vaginosis (CV) is a condition where lactobacilli overgrow and begin damaging vaginal cells, causing burning, irritation, soreness and thick white discharge that resembles a yeast infection. Because lactobacilli normally form the healthy part of the vaginal microbiome, CV often goes undiagnosed.

CV appears to be driven by excess glycogen, hormonal influences such as oestrogen dominance, metabolic disturbances, histamine issues and blood sugar dysregulation. Lactulose and probiotics often worsen symptoms by feeding lactobacilli.

Temporary overgrowth resolves once triggering probiotics or prebiotics are stopped. True CV persists because of underlying hormonal or metabolic drivers that cause a single lactobacillus species to dominate.

Symptoms include burning, itching, soreness, dyspareunia, irritation, and thick white discharge. Vaginal pH remains acidic (3.5–4.0), and symptoms often worsen around ovulation.

Microbiome testing analysed by an experienced practitioner or skilled wet mount microscopy can confirm CV. Repeated yeast treatment failure and worsening symptoms from probiotics are strong clues.

Oestrogen spikes increase vaginal glycogen, feeding lactobacilli and triggering a surge in lactic acid production, which worsens symptoms.

CV shows near-total dominance of a single lactobacillus species, low or normal pH, no yeast or BV-associated bacteria, and few white blood cells.

Diagnosis is based on ruling out yeast and BV, checking pH, identifying extremely high lactobacillus counts and assessing symptoms alongside laboratory findings.

Baking soda raises vaginal pH, temporarily reducing lactobacillus numbers and relieving irritation. It may be used as a douche or suppository.

Some relief may occur immediately, but full results usually develop over several weeks. Overuse of bicarbonate should be avoided.

Seek a practitioner experienced with CV. Persistent symptoms often indicate hormonal, metabolic or biochemical contributors that require deeper investigation.

Yes. Probiotics containing lactobacilli, and prebiotics such as lactulose, can worsen CV by feeding the overgrowth.

No. A healthy vagina may have high lactobacilli without symptoms, but CV only occurs when lactobacilli cause irritation and cell damage.

CV may represent 5–7% of cases of discharge that resemble thrush but do not respond to antifungals. It is frequently overlooked in clinical settings.

Related Posts

References4–10

- 1.Cerikcioglu N, Beksac MS. Cytolytic Vaginosis: Misdiagnosed as Candidal Vaginitis. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Published online 2004:13-16. doi:10.1080/10647440410001672139

- 2.Wathne B, Holst E, Hovelius B, Mårdh PA. Vaginal discharge – comparison of clinical, laboratory and microbiological findings. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. Published online January 1994:802-808. doi:10.3109/00016349409072509

- 3.Voytik M, Nyirjesy P. Cytolytic Vaginosis: a Critical Appraisal of a Controversial Condition. Curr Infect Dis Rep. Published online August 12, 2020. doi:10.1007/s11908-020-00735-w

- 4.Cibley LJ, Cibley LJ. Cytolytic vaginosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Published online October 1991:1245-1249. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90736-x

- 5.Varma K, Kansal M. Cytolytic vaginosis: A brief review. JSSTD. Published online April 30, 2022:206-210. doi:10.25259/jsstd_41_2021

- 6.Puri S. Cytolytic vaginosis: A common yet underdiagnosed entity. Ann Trop Pathol. Published online 2020:29. doi:10.4103/atp.atp_18_19

- 7.Bhat R, Suresh A, Rajesh A, Rai Y. Cytolytic vaginosis: A review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. Published online 2009:48. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.55490

- 8.Hu Z, Zhou W, Mu L, Kuang L, Su M, Jiang Y. Identification of Cytolytic Vaginosis Versus Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. Published online April 2015:152-155. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000076

- 9.Kraut R, Carvallo FD, Golonka R, et al. Scoping review of cytolytic vaginosis literature. Wani FA, ed. PLoS ONE. Published online January 26, 2023:e0280954. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280954

- 10.Yang S, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wang J, Chen S, Li S. Clinical Significance and Characteristic Clinical Differences of Cytolytic Vaginosis in Recurrent Vulvovaginitis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. Published online June 15, 2016:137-143. doi:10.1159/000446945