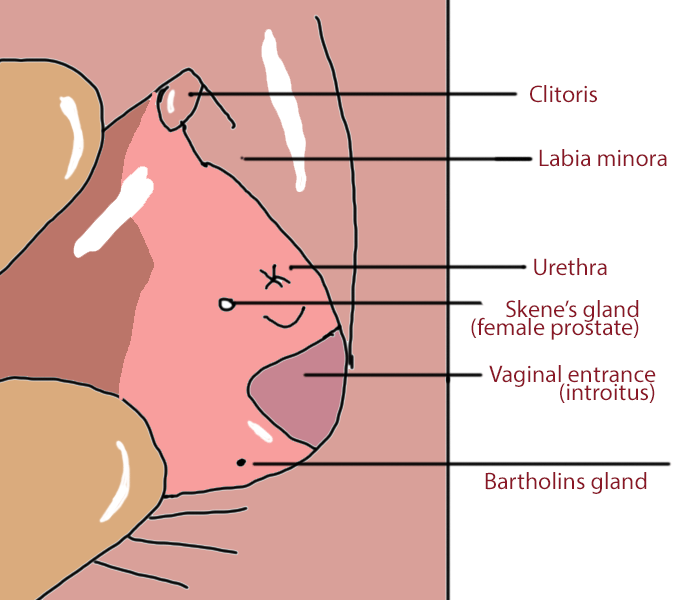

The Skene’s glands are located on the upper wall of the vagina, and the ducts empty out around the lower end of the urethra. The Skene’s glands are made of the same cells as the male prostate and are known as a homologue (‘same as’).

Skene’s glands are also called the lesser vestibular, periurethral, or paraurethral glands, or, increasingly, the more correct name of the female prostate1.

The Skene’s glands drain via the Skene’s ducts into the urethra and near the urethral opening to lubricate the area. These glands are surrounded by tissue that includes a part of the clitoris extending up into the vagina. This tissue swells up with blood during sexual arousal, and the female prostate – Skene’s glands – produces some white fluid.2

The never-ending debate about female ejaculation, whether it even exists, etc., was discussed in Emanuele Jannini’s 2002 paper, whereby Jannini found that there are highly variable anatomical expressions of the Skene’s glands, with sometimes glands missing entirely in some people.

This means that if Skene’s glands cause female ejaculation and so-called ‘g-spot orgasms‘, and some of you have no idea what we’re talking about, an anatomical difference may be the ‘why’.

Composition of female prostatic fluid

In some women, the female prostatic secretion exits from the urethra upon sexual stimulation. The viscous white secretion that appears to be produced by the Skene’s glands is very similar in composition to prostatic fluid, including specific proteins and enzymes (Human Protein 1 and PDE5).

The fluid has lower levels of creatinine but elevated levels of prostate-specific antigen, prostatic acidic phosphatase, prostate-specific acid phosphatase, and glucose.

When examined closely, the male prostate and Skene’s glands appear to operate very similarly. This is why researchers are now starting to call Skene’s glands the female prostate.

The female prostate exists, but bizarrely, most diagrams of female reproductive anatomy do not include the ducts to these glands (the outside exit point) at all. You could be forgiven for thinking these glands do not exist.

As mentioned, problematically, sometimes the glands and ducts may appear not exist, complicating the issue.

Clinical implications of the Skene’s glands

The female prostate is important clinically for several reasons. The first is it can be the origin of infections and cancer. Additionally, HIV infection may occur here3.

Some sexual assault cases may have mistakenly resulted in potentially innocent men being found guilty based on the presence of PSA at a time when it was believed that women did not have prostates and could, therefore, not produce PSA4.

Prostate-specific Antigen (PSA) and Prostate-specific Acid Phosphatase (PSAP)

Women produce PSA from the prostate, of which elevated levels are one of the signs of cancer in the prostate in both men and women.

Does female prostatic fluid serve an antimicrobial purpose?

Researchers looked into women who could ejaculate and whether these secretions had an antimicrobial component deposited into the urethra.

The team postulated that the secretions meant the woman was less likely to develop a urinary tract infection (UTI), particularly sex-induced UTI.2

Female ejaculation (‘squirting’)

The bigger the Skene’s glands, the more of a ‘squirter’ a person is. Female ejaculation has been a complex topic because, as previously mentioned, not all people with vaginas are able to do it, while others can’t help it.

The smaller white secretions we’ve discussed here aren’t quite the same as what female ejaculators describe – a small deposit of fluid versus the huge gush of watery liquid produced during ‘squirting’.

History and discovery of the Skene’s glands

Anatomist Regnier de Graaf recognised the female prostate in 1672. In 1880, Alexander Skene brought attention back to these glands and ducts, which is why they are called Skene’s glands and ducts.

There is a move now to refer to these glands as the female prostate since that is the more accurate term for them.

Things that can go wrong with your Skene’s glands

References

- 1.Zaviačič M, Ablin RJ. The Female Prostate. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Published online May 6, 1998:713-713. doi:10.1093/jnci/90.9.713

- 2.Moalem S, Reidenberg JS. Does female ejaculation serve an antimicrobial purpose? Medical Hypotheses. Published online December 2009:1069-1071. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2009.07.024

- 3.Ablin RJ. HIV-Related Protein in the Prostate: A Possible Reservoir of Virus. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. Published online May 1, 1991:579-579. doi:10.1093/ajcp/95.5.759b

- 4.Longo VJ. The female prostate. Urology. Published online July 1982:108-109. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(82)90556-8