Urethral pain syndrome presents with many of the same symptoms of a urinary tract infection, but a urine test for pathogens comes back low or negative.

Pain is recurrent and has no obvious cause. Studies are infrequent and treatment strategies vary widely between practitioners.

Urethral pain syndrome was so named in 2002 by the International Continence Society, with the syndrome formerly known as urethral syndrome or urethritis. It is now amongst conditions grouped together as genitourinary pain syndromes. 1

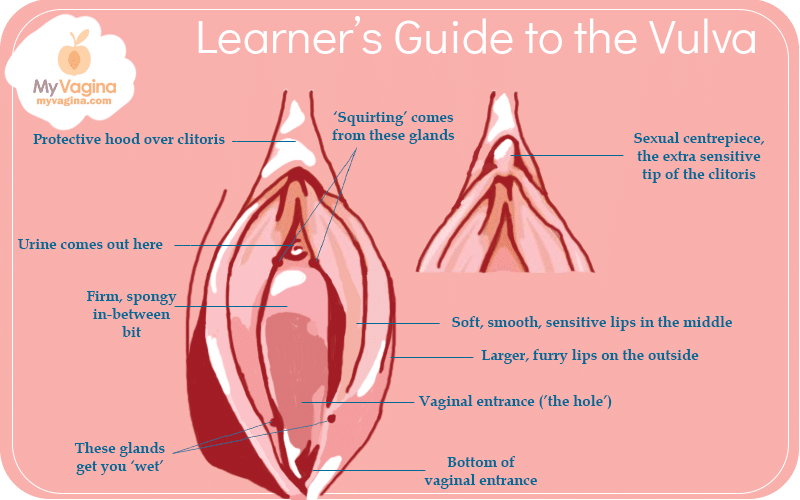

Understanding the anatomy

The urethra is the tube that connects the bladder to the external opening where urine is released out of the body. It sits between the clitoris and the vaginal opening, with the Skene’s glands as neighbours.

Symptoms of urethral syndrome

- Pain or discomfort while urinating

- The urge to urinate frequently

- A sudden sense of urgency to urinate

- Not feeling like the bladder is ever empty

- Lower back pain

- Genital pain

- The urethral exit-point on the vulva may be tender

- Pain during sex (dyspareunia)

- Discomfort of the vulva

- Discomfort of the lower abdominal area

Diagnosis of urethral syndrome

A urine test will be conducted. At times, a blood test and cystoscopy (a small telescope is used to check the bladder and urethra) may be conducted. Make sure you are tested for Mycoplasma genitalium.2

The urine test for urinary tract infections looks for red and white blood cells. The white blood cells are what your body responds to inflammation with, so if you have an infection that is causing inflammation, you will have white blood cells in your urine.3

A doctor will also do a culture to see what type of bacteria are in your urine, and in what quantities. Cultures are not an exact science, and precise information may not be available unless your test is a PCR or NGS test.

If you have an infection, you do not have urethral syndrome, which is characterised by inflammation of the urethra, but without infection.

Causes of urethral syndrome

Irritants

Urethral pain syndrome may be a form of contact dermatitis – that is, an inflammatory response to an irritant like soap or laundry detergent.

Low-grade or undiagnosed infection

Urethral syndrome may be caused by an undiagnosed infection, such as a sexually transmitted infection or mycoplasmal infection that is not picked up on culture.

Oestrogen deficiency

Those in menopause sometimes get urethral syndrome because of the drop in their oestrogen levels, which in turn creates inflammation and thinning of the area around the urethra and vagina.

Urinary irritants – food and drink

Sometimes, certain foods or drinks can cause irritation to the urinary tract, for example, alcohol, caffeinated drinks or spicy food.

Early interstitial cystitis (IC) (painful bladder syndrome)

The inflammation and pain caused may be due to a condition known as interstitial cystitis, or painful bladder syndrome. The cause of IC is unknown.

Narrowed urethra (urethral stenosis or stricture)

If the urethra becomes narrowed, it can cause discomfort or pain as urine pushes through.

Low mucosal barrier strength

All ‘wet’ surfaces in the body have a layer of mucous that protects them, known as the mucosal barrier. A deficiency in the mucosal barrier may contribute to inflammatory changes.

Contact dermatitis

This conditoin may be caused by irritation from chemicals found in pads, tampons, soaps or (printed) toilet paper, especially low-quality versions of these items that contain irritants.

Symptoms could be a reaction to condoms, semen, contraceptive devices, or spermicide.

Items that may touch the vulva include:

- Wipes (moistened towelettes, make-up wipes, toilet wipes, baby wipes)

- Soap

- Body wash/shower gel

- Bubble bath

- Moisturiser

- Laundry detergent

- Dryer balls/washing machine balls

- Douches or feminine washes

- Condoms

- Lubricant

- Spermicide

- Semen

- Anything on hands or toys during masturbation

- Tampons

- Pads

- Pantyliners

- Menstrual cups

Skenitis (prostatitis)

Skene’s glands in the vulva – right next to the urethral opening – are the same base tissue as the prostate in the biologically male reproductive tract, sometimes called the female prostate. These glands or ducts can become inflamed.

Inflammation of the female prostate glands (prostatitis) – called Skenitis in relation to biological females – may cause similar symptoms to urethral pain syndrome. 4

Local inflammation, spasm

Inflammation of surrounding tissue might also be a factor, causing spasm in the muscles around the urethra.

Treatments for urethral syndrome

Treatments vary considerably between practitioners. 5 Trial and error is likely to be the only practical way forward.

If symptoms are being caused by outside influences like printed toilet paper, treatment is to remove the irritant. Figuring out irritants can be harder than it seems, but do a thorough inventory.

You may be given a cycle of antibiotics, despite the test saying pathogen counts are low or absent.

Many urologists prescribe a urinary tract-targeted pain reliever if the patient is in severe pain and discomfort, though other drug treatments may include antibiotics, alpha-receptor blockers, topical oestrogen or muscle relaxants.6

If you experience symptoms during and after sex, you may be asked to refrain from sexual activity until your condition is controlled. You may also be given steroid shots in the urethra to control inflammation.

If low oestrogen is causing tissue weakening, pelvic physiotherapy, high-tech laser or radiofrequency treatments or hormone therapy may be recommended.

Surgery is considered a last resort, but depending on the cause, may be recommended. 7

Pelvic physiotherapy may be recommended. 8

Other treatments may include topical steroids, urethral dilation, local anaesthetic, mucosal protecting agents, acupuncture, antidepressants and bladder training.

References

- 1.Ivarsson LB, Lindström BE, Olovsson M, Lindström AK. Treatment of Urethral Pain Syndrome (UPS) in Sweden. Rosier PFWM, ed. PLoS ONE. Published online November 22, 2019:e0225404. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225404

- 2.Gaydos CA. Mycoplasma genitalium: Accurate Diagnosis Is Necessary for Adequate Treatment. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. Published online July 15, 2017:S406-S411. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix104

- 3.Masajtis-Zagajewska A, Nowicki M. New markers of urinary tract infection. Clinica Chimica Acta. Published online August 2017:286-291. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2017.06.003

- 4.Gittes R, Nakamura R. Female urethral syndrome. A female prostatitis? West J Med. 1996;164(5):435-438. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8686301

- 5.Phillip H, Okewole I, Chilaka V. Enigma of urethral pain syndrome: Why are there so many ascribed etiologies and therapeutic approaches? Int J Urol. Published online January 21, 2014:544-548. doi:10.1111/iju.12396

- 6.Phillip H, Okewole I, Chilaka V. Enigma of urethral pain syndrome: Why are there so many ascribed etiologies and therapeutic approaches? Int J of Urology. Published online January 21, 2014:544-548. doi:10.1111/iju.12396

- 7.Hoag N, Chee J. Surgical management of female urethral strictures. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(Suppl 2):S76-S80. doi:10.21037/tau.2017.01.20

- 8.Dreger NM, Degener S, Roth S, Brandt AS, Lazica DA. Das Urethralsyndrom: Fakt oder Fiktion – ein Update. Urologe. Published online September 2015:1248-1255. doi:10.1007/s00120-015-3926-9

Get a fresh perspective with a qualified, experienced vulvovaginal specialist naturopath.

This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageThe most comprehensive vaginal microbiome test you can take at home, brought to you by world-leading vaginal microbiome scientists at Juno Bio.

Easy-to-use BV and AV treatment program.

Promote and support a protective vaginal microbiome with tailored probiotic species.