Introduction to hormonal IUDs and their impacts on the body

Hormonal IUDs are those containing either high or low-dose levonorgestrel, a synthetic hormone that behaves unlike any other hormone in the body. The impacts of levonorgestrel on the female body combine to prevent pregnancy.

Hormonal IUDs are also commonly used to stop or slow excessive or problematic menstrual bleeding, for example, heavy periods or in menstrual disorders such as endometriosis.

What is progestin, and what does it do?

Levonorgestrel is what’s known as a progestin, a synthetic (manmade) hormone that fits into progesterone receptors and exerts a progesterone-like effect.

A hormone is like a key; the receptor is the lock. The key in the lock opens the door, which is the ‘action’ of the hormone. Hormones are messengers.

How to pronounce levonorgestrel

Leaven – orr – jest – trawl

The difference between hormonal and copper IUDs

An intrauterine device (IUD) is placed in the uterus via the vagina, where it stays for several years as a long-acting form of birth control. There are two types of IUD – copper (Paragard) and hormonal (Mirena, Liletta, Kyleena and Skyla). Copper IUDs do not contain hormones.

Copper IUDs work by introducing copper ions into the uterine lining, which deters the implantation of a fertilised egg. With hormonal IUDs, the action is produced by a localised hormonal component that is, in theory, only supposed to affect the uterus and cervix.

Hormonal IUDs cause significant inflammation and immune response, whereas the copper IUD does not. (It has its own problems, but they’re not the same problems.) Some hormones can be absorbed from the hormonal IUD into systemic circulation, however, having secondary impacts.

The mechanisms and actions of hormonal IUDs

How the hormonal IUD changes periods

In the uterus, progestins in the hormonal IUD act, in some ways, like progesterone, and block the action of estrogen. As a result, the endometrial lining (which eventually becomes your period) doesn’t flourish as much. Many people find their periods change and get lighter, become unpredictable or may disappear altogether when using the hormonal IUD.

Normally, progesterone and estrogen work together to keep the endometrial lining stable and abundant. Estrogen builds up and thickens the lining, and then progesterone steps in at ovulation to keep the lining from getting too thick. These two hormones keep each other in check.

With hormonal IUDs, the progestin doesn’t allow the estrogen to build the endometrial lining, instead limiting estrogen’s action significantly. This is how hormonal IUDs slow, heavy menstrual bleeding.

The mucous plug that keeps sperm and bacteria out of the uterus

Progestins (and real progesterone) thicken cervical mucous, providing a physical barrier between sperm and egg, and block any unwelcome bacterial guests entering the uterus via the cervix.

In this sense, progestins help keep infections out of the uterus and upper reproductive organs, as progesterone does in only the second half of the menstrual cycle.

How ovulation can be suppressed

Because some of the hormones from the Mirena, Liletta, Skyla and Kyleena enter systemic circulation, ovulation may be suppressed. The hormonal messengers from the brain aren’t strong enough to trigger a response in the ovary, so nothing much happens.

Other birth control that suppresses ovulation in the same way with the same hormone are:

- Oral contraceptive pill

- Depo-Provera contraceptive injection

- Progestin-only birth control pills (‘mini pill‘)

- Emergency contraception (Plan B, the morning-after pill)

- Contraceptive implants

How hormonal IUDs prevent pregnancy

- Thickens cervical mucous so sperm can’t physically get into the uterus.

- Blocks the hormonal cascade that results in ovulation (more common in high-dose IUDs). No egg exists to fertilise, even if sperm does get through the mucous.

- Thins the endometrial lining to prevent implantation of a fertilised egg, should the sperm get through the mucous and ovulation occurs.

Is my hormonal IUD high or low dose?

High-dose hormonal IUDs include Mirena and Liletta, both releasing around 20mcg of levonorgestrel into the uterus each day. Mirena is approved for use for 5-6 years, while Liletta for eight.

Low-dose hormonal IUDs include Kyleena and Skyla. Kyleena releases about 17.5mcg per day, while Skyla is the lowest dose, releasing 14mcg per day. Kyleena is approved for use for five years, and Skyla for three.

Dose does matter. The more levonorgestrel is available for absorption into the body (not just the uterus), the more can potentially be absorbed and create secondary impacts like a higher risk of BV.

Impact on vaginal and systemic health

The link between hormonal IUDs and bacterial vaginosis (BV)

Research shows that hormonal IUDs don’t tend to cause ongoing vaginal microbiome issues in most users. Any impacts tend to be temporary and resolve a few months after insertion.

However, some users report an increase in recurrent BV or other vaginal infections. Here, we explore how and why this might be happening.

How does a hormonal IUD result in BV?

The hormonal IUD may exacerbate an already-present microbiome imbalance, causing the emergence of symptoms. Or, it could impact systemic hormone messengers and levels, having some negative outcomes for the whole body and the vaginal microbiome.

How many users don’t ovulate?

The suppression of ovulation is found in about half of all users for at least the first year after high-dose hormonal IUD placement, the Mirena and Liletta, sometimes longer.

Suppression of ovulation is found less often (10-25% of cycles) in low-dose IUD users, Skyla and Kyleena. Ovulation may be suppressed in all or only some menstrual cycles.1

Is everyone affected equally?

Some users may be more sensitive to the effects of the hormonal IUD than others, with several factors at play, including genetics, low body fat (fat cells are required in part for estrogen production), metabolism of hormones, those nearing menopause, and baseline hormonal status. The effect is more pronounced with the use of high-dose hormonal IUDs.

Why do doctors and research always say not much hormone is absorbed?

The manufacturers and many doctors continue to purport that a low amount of the hormone in the IUDs is absorbed into the body. But, the fact remains that around half of users stop ovulating for the first year at least, with 25% still having anovulatory cycles after four years. Mirena manufacturers state this in their product information.

The Mirena information document states: “Ovulation is inhibited in some women using Mirena. In a 1-year study, approximately 45% of menstrual cycles were ovulatory, and in another study after 4 years, 75% of cycles were ovulatory.”

Or, in other words, 65% of menstrual cycles in the first year were anovulatory (well over half), and after four years, 25% of cycles of users of the Mirena suppressed ovulation. This is significant.

This information shows that the hormone is being absorbed and, therefore, can have a much more significant effect on the body and other hormones for many years in some people than is being acknowledged.

If you have experienced side effects from the hormonal IUD that you’re being told are not possible, you are not crazy, you may be being medically gaslit.

Next, we’ll go through each element of the potential impacts of hormonal IUDs that could contribute to or cause BV. This is dense, but super interesting, so buckle up.

The effect on progesterone, testosterone and estrogen

Levonorgestrel, the synthetic hormone in the hormonal IUD, is derived from testosterone. Due to its physical similarities with progesterone and testosterone, levonorgestrel fits into and activates both progesterone and testosterone receptors.

Thus, in the uterus and surrounding tissue, levonorgestrel can exert both progesterone-like and testosterone-like activity, but not doing either job particularly well when compared to real or bioidentical progesterone and testosterone.

Some of the benefits of real progesterone or testosterone don’t occur, and some unintended consequences can develop in the vaginal environment, which can result in BV and other issues.

But, that’s not all. The hormonal IUD can also negatively affect estrogen levels, which can prove detrimental to the vaginal environment.

Estrogen levels can drop on the hormonal IUD

In some users, estrogen levels may be reduced when the levonorgestrel is absorbed and enters systemic circulation. The hormonal cascade that tells the ovaries to produce estrogen and trigger ovulation can be interrupted by the synthetic hormone in the IUD.

The IUD hormones interrupt the hormonal messaging system (the HPO axis); the messages from the brain telling the ovary what to do aren’t strong enough to cause the action. The result can be less estrogen production and a lack of ovulation.

Estrogen supports protective bacteria in the vagina

Along with the vital role of ‘ripening’ or maturing vaginal cells, estrogen stimulates the production of glycogen in vaginal cells. Glycogen is the sugar that feeds protective lactobacilli species. Estrogen also promotes healthy vaginal cells, vaginal moisture, and a healthy menstrual cycle.

With a drop in estrogen, protective species in the vagina may go hungry, and colony counts may drop, sometimes dramatically. There is always a keen BV-related bacteria on the sidelines ready to take the lactobacilli’s place as it drops off the perch.

Estrogen is your friend

Vaginal cells are very estrogen-sensitive, and a loss of vaginal estrogen can result in symptoms associated with vaginal atrophy, such as dryness and fragility of tissue. Other symptoms of low estrogen include hot flashes, night sweats and lowered libido. These symptoms are more likely the closer to menopause you are.

The effect of the hormonal IUD on progesterone

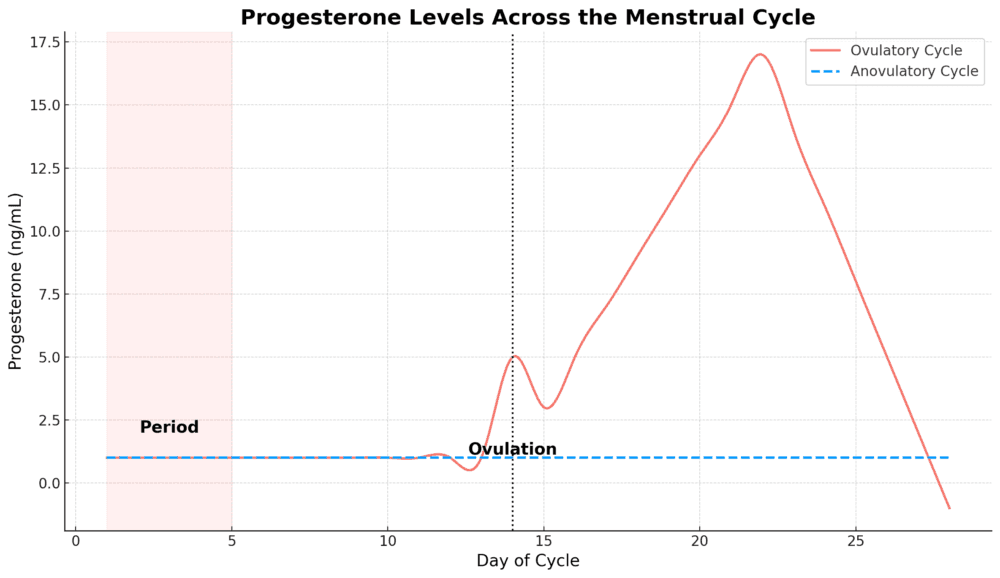

Ovulation suppression causes the huge loss of almost all natural progesterone

But, this isn’t the only way lactobacilli species may be starved out when using the hormonal IUD. In fact, the much greater threat to the vagina is the loss of ovulation, which could cause a possibly enormous decline in natural progesterone production.

When the hormones from the IUD are absorbed into the body and suppress ovulation, the natural production of ovulation-driven progesterone is halted. This can be a serious problem for the vaginal ecosystem.

How do we get natural progesterone?

Progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum (the ‘egg sac’) after the egg has burst out to continue its journey. Progesterone is secreted almost right up until the next menstrual period starts.

Progesterone production peaks around Cycle Day 21 (if Cycle Day 1 is the first day of your last period), around seven days post-ovulation. Meaning, you only get two weeks of progesterone if you’re ovulating.

Progesterone is a very important hormone for the vagina from multiple standpoints, and the loss of ovulation and natural progesterone can spell trouble. While the word progestin may seem close to the word progesterone, these two hormones are not at all equivalent.

Note: Naturally produced human progesterone, also known as endogenous progesterone, is equivalent to what’s known as bioidentical progesterone, often used in hormone therapy, particularly in the USA.

Bioidentical hormones behave just like the real deal. IUDs do not use bioidentical progesterone, just synthetic progestins, but these real-deal bioidentical hormones are available from a doctor as tablets, gels, creams or patches.

Progesterone and vaginal tissue

Actions and benefits of real (or bioidentical) progesterone

- Thickens and strengthen vaginal and pelvic tissue, including the pelvic floor

- Inhibits the enzyme that breaks down collagen in pelvic tissue

- Supports healthy blood vessels and promotes blood flow

- Triggers vaginal epithelial cells to shed and renew

- Promotes vaginal secretions and moisture

- Has an anti-inflammatory effect on vaginal tissue

- Modulates vaginal immunity

The impact of a loss of vaginal epithelial cell shedding

Progesterone causes the regular shedding of the outermost layer of vaginal epithelial cells, which line the vaginal canal. If you put your finger into your vagina, you are touching the epithelial cells.

While estrogen helps these cells ‘ripen’ or mature, progesterone causes them to fall off (shed), revealing a fresh layer of cells. These shed cells are the primary source of glycogen (lactobacilli food) in the vagina. Thus, in a low progesterone environment, shedding decreases, lactobacilli starve, and their colony will be depleted.

Lactobacilli protect the vagina in many ways. Without their fierce competition for vaginal real estate, BV-related bacteria may take their place.

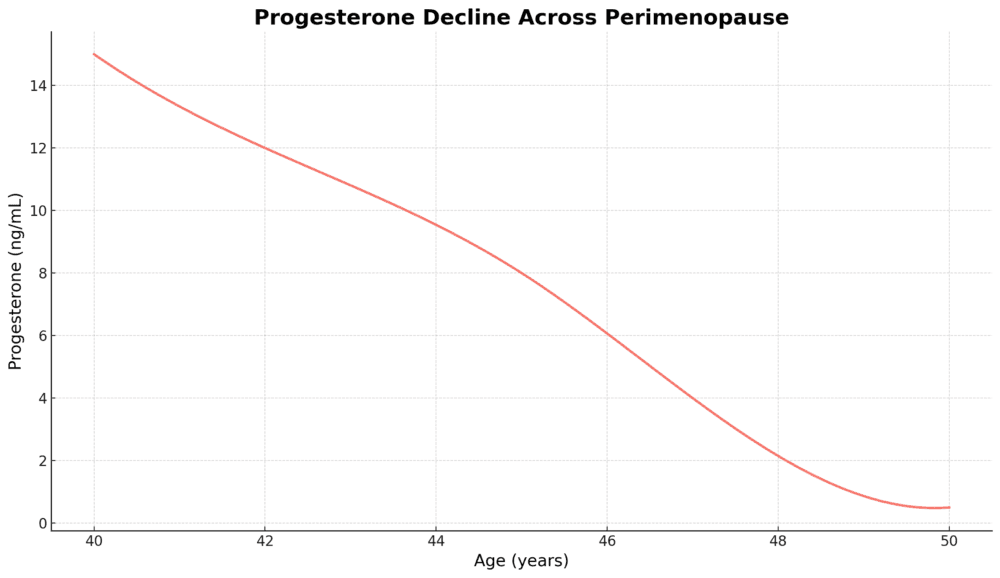

The loss of progesterone can be even more profound in perimenopause (age 42+)

Perimenopause generally starts in our early 40s, because progesterone starts to decline. Progesterone is the first hormone to drop, which occurs steadily across our 40s. The ovulation egg sac starts to secrete less progesterone.

This decline in progesterone is a long process and may go unnoticed for a while. Symptoms may be attributed to other causes. Even doctors don’t understand this process very well! But, the impacts of the loss of progesterone can be profound and are significant.

The loss of ovulation and progesterone in your 40s due to the hormonal IUD can wreak havoc on your body and vaginal microbiome. The closer to menopause you are, the more severe the impacts.

As menopause approaches, the ovaries slow down and stop producing estrogen. When ovulation and periods stop for 12 consecutive months (which can be well into one’s 50s), menopause occurs, and postmenopause begins.

The subsequent loss of estrogen can result in an increased risk of BV and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Having birth control up until menopause can be very important, and the hormonal IUD is often prescribed.

Broader systemic impacts

How progesterone impacts pelvic and vaginal tissue

Progesterone is deeply important in the vaginal environment, ensuring vaginal elasticity and tissue thickness.

Progesterone relaxes skeletal and smooth muscle, including the pelvic floor. When progesterone is low or largely absent, an overly tight pelvic floor and painful period cramps may result due to a lack of natural relaxation of these muscles.

A relaxed muscle allows blood flow in and out, while a tight muscle limits oxygen and blood flow, causing cramping and pain.

But that’s not all, folks…

The loss of progesterone has a much more significant impact on pelvic tissue than just muscle tension. The enzyme that breaks down collagen in pelvic tissue, collagenase, becomes more active in a low progesterone environment.

That’s right. Collagen – the substance that holds us up and keeps us firm forever – is degraded far quicker when you aren’t ovulating and receiving the progesterone gifts from the egg sac (the corpus luteum).

Understanding the impact of collagenase enzymes in the vagina

Collagen turnover is normal, but as we age, less collagen is produced, and the existing collagen degrades – think wrinkles, creepy skin and less flexibility. A low progesterone environment will speed this collagen degradation up.

To add insult to injury, progesterone dampens inflammation, so a low progesterone environment results in greater inflammation. Collagenase is more abundant in inflammation.

Increased collagenase activity breaks down collagen all over the body faster (yes, progesterone is anti-ageing!).

Progesterone inhibits or slows this collagenase enzyme, so collagen breakdown occurs more slowly in the uterus, cervix, vagina and pelvic floor when progesterone levels are normal – after ovulation. If the hormonal IUD is suppressing ovulation, you don’t have much progesterone.

The effects of low progesterone on collagen in pelvic tissue

Collagen is a major structural protein in connective tissue. Increased rates of breakdown of collagen result in weaker pelvic floor muscles and less robust vaginal and pelvic tissue.

Persistently low progesterone can result in a dryer, thinner vagina, and poorer pelvic connective tissue strength. As connective tissue weakens, blood flow reduces, and the risk of uncomfortable symptoms increases.

Sex might become uncomfortable, the risk of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence increases, inflammation increases and the environment becomes decidedly less friendly for protective species of bacteria.

Ultimately, the degradation of the pelvic and vaginal tissue can result in the loss of your protective microbial army and, amongst other issues, increase the risk of recurrent BV.

Progesterone supports vaginal moisture and protection

Progesterone contributes to cervical mucous production and secretions, which provide protection from infections and contribute to vaginal comfort, lubrication and moisture.

As vaginal epithelial cells are shed under the influence of progesterone, the vaginal lining is refreshed and renewed. This mature cell turnover is not only key for feeding protective lactobacilli with the glycogen payload but is also important for structural strength and vaginal lubrication.

Progesterone and the vaginal immune system

Progesterone plays a vital role in the modulation of vaginal immunity and reducing inflammation. Progesterone enhances the communication between two special immune cells whose job is to capture and kill invading pathogens.

Enhanced communication between our friends, neutrophils and macrophages, and promotes pathogen elimination.2

Antibody army at the ready

Progesterone also increases Langerhans cell numbers, special cells that are essential for providing antigens in vaginal epithelial cells3.

Antigens are substances produced by these special cells that tell the body to send out antibodies to attack foreign invaders. Antigens are a very important component of our immune system and play an important role in vaginal immunity and avoiding infections.

Causing and curing vaginal inflammation, waving down the immune troops – cytokines and chemokines

Under the influence of progesterone, special immune mediators, cytokines and chemokines, are produced in cervicovaginal fluid4.

Cytokines can be pro- or anti-inflammatory, while chemokines use their wiles to attract various immune cells to the area when required to deal with unwanted guests.

An excellent triage nurse – vaginal immunity is a balancing act

Progesterone supports protective vaginal flora while ensuring any incoming semen and sperm and disruptive bacteria/pathogens are managed appropriately2. This immune modulation ensures protective flora can thrive while infections are prevented.

Real progesterone is an anti-anxiety and sedative

Endogenously produced natural progesterone has an anti-anxiety and sedative effect. Levonorgestrel, by contrast, does not have this benefit.

Progesterone modulates our calming neurotransmitter receptors in the brain. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a powerful relaxing force, and without the addition of progesterone, the action of GABA may be depleted.

Low progesterone is associated with a poorer experience of ‘you’ on a day-to-day basis, with increases in mood swings, anxiety, panic attacks and premenstrual syndrome (PMS). The hormonal IUD may be a direct cause of low progesterone.

Many healthcare providers do not understand the deep connection between the loss of progesterone due to a lack of ovulation on a hormonal IUD and the development of sometimes very severe psychological symptoms, let alone vaginal microbiome disturbances.

Why? The mistaken belief is that not much of the hormones are absorbed into the systemic circulation, therefore this impact isn’t possible.

Even some of the best vagina doctors in the world still believe that most users do not have suppressed ovulation, when the evidence5,6 clearly shows that around half do, for at least the first year, if not longer.

The impact on testosterone

Testosterone activity and the hormonal IUD

Absorption of levonorgestrel into the body from IUDs can affect the overall effect of testosterone, since the synthetic hormone ‘key’ fits into the hormone receptor ‘locks’ of both progesterone and testosterone. Levonorgestrel can bind to testosterone receptors and, in part, ‘ act’ like testosterone. Just not the real deal.

When levonorgestrel binds to a testosterone receptor (remember, the key fits into a lock to open a door), the impact is weaker than natural testosterone.

Overall, a small reduction in the androgenic effect may occur as the hormonal stranger blocks stronger, real testosterone from fitting into the lock. This means testosterone-sensitive tissue, including that found in the vagina, is not affected as much. Depending on the baseline testosterone level, this may be a benefit or a pitfall.

What is SHBG, and how does it affect testosterone levels?

The hormonal IUD can reduce circulating free testosterone levels by increasing sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) in some users. As the name suggests, SHBG binds testosterone, making it unavailable to fit into any receptors. The key no longer fits anywhere. If SHBG has got the testosterone, it is biologically unavailable.

If someone has androgenic symptoms like hair growth where you don’t want it, acne, or male pattern hair loss, the IUD hormones may reduce these symptoms by reducing overall bioavailable testosterone. In those with low testosterone, the impact may be the opposite and contribute to more masculine symptoms.

Testosterone and the vagina

Testosterone supports healthy gland activity and mucosal secretions in the vagina. Thus, any reduction in testosterone’s effect may lead to vaginal dryness and reduced lubrication. This effect is likely to be most apparent in those with already low baseline testosterone.

Androgens also promote vaginal elasticity and thickness of vaginal tissues by encouraging collagen synthesis and strong tissue. Vaginal tissue may become less resilient when levonorgestrel is absorbed systemically and is taking the place of real testosterone.

Symptoms of changes to testosterone effect in the vagina

Changes to testosterone’s impact on vaginal tissues can result in discomfort during sex, and vaginal atrophy, especially when combined with lower estrogen. Subtle changes might include vaginal dryness or irritation.

But, significantly, in vaginal infections like BV, testosterone levels affect glycogen levels of the shed vaginal epithelial cells. Remember, glycogen is the special sugar in ripened, mature vaginal epithelial cells that feed protective lactobacilli species.

The hormonal IUD’s impact on testosterone can interrupt the glycogen balance, leading to less microbiome resilience and an increased risk of BV and yeast infections.

This impact is likely to be relatively minor in someone with otherwise normal estrogen and testosterone levels. However, for anyone in perimenopause or with already low testosterone, the impact may be greater.

Additional considerations

Biofilms are easy to build on an IUD surface

Last, and perhaps least interesting, the IUD and its string can contribute to vaginal microbiome disturbances because the surfaces provide a suitable platform for bacterial biofilm development.

Biofilms are a sticky coating, or film, built on top of cells that allows BV-related bacteria to hide from treatments such as antibiotics. Biofilms can provide a haven for disruptive bacteria and offer a reservoir of bacteria that resist otherwise helpful treatments.

Smooth surfaces like IUDs and catheters don’t fight back, making an excellent surface to build a BV biofilm.

Biofilms promote the disruptive bacteria that share and strengthen them, which we see in BV. Multiple bacterial species fortify the vaginal environment and biofilm to their tastes, evading efforts at eradication and actively fighting off takeover attempts by other bacteria, including lactobacilli species, from (re)entry.

However, it’s helpful to note that a microbiome disruption would already have had to be in play before the IUD insertion or another factor caused a shift post-insertion, which we have discussed.

The plastic device, by itself, in an otherwise healthy vaginal microbiome does not cause BV. A strong, protective microbiome would not allow this shift to BV to occur. The environment must change for BV to develop.

Quick list of impacts

- May cause the suppression of ovulation (reduces estrogen and progesterone)

- May cause a decrease in estrogen (loss of healthy bacteria food, reduction in blood flow and vaginal health overall)

- May cause a decrease in progesterone (reduction in vaginal elasticity, anti-inflammatory and immune effects in the vagina, broader loss of anti-anxiety and sedative effects)

- May cause a decrease or increase in testosterone effect (may result in decrease of vaginal moisture, or worsening systemic effects like acne)

- May reduce vaginal moisture levels (decrease in vaginal hormone action)

- May reduce vaginal tissue strength and structural integrity (decrease in vaginal hormone action, especially progesterone and estrogen)

- May increase the risk of prolapse, pelvic floor dysfunction and microbiome disturbances (increased loss of collagen and strength of pelvic structures)

Recommendations and next steps

What to do next

If you suspect the IUD is responsible for your never-ending merry-go-round of BV, there are only two real options: have it removed or plug the gaps of the hormonal and other impacts the best you can.

Sometimes, the hormonal IUD is just the best option for now, and that’s ok – as long as you get good support and advice to navigate the problems it can cause. An unwanted pregnancy can be a much bigger problem.

How to remove the IUD

If you want to remove your own IUD yourself at home, you can – find instructions here (PDF). Otherwise, book with your healthcare practitioner to have it removed, the sooner the better.

Working around the issues

To work on the hormonal impacts and particularly if you are in perimenopause (aged 42 or over), book with an experienced My Vagina clinical naturopath for one on one support. We can help.

Options include supporting hormone levels, treating the vaginal microbiome effectively, and discussing options for the future.

References7–12

- 1.Espey MD, MPH E, Hofler MD, MPH, MBA L, Gynecology and the Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group . Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Implants and Intrauterine Devices. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2024. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2017/11/long-acting-reversible-contraception-implants-and-intrauterine-devices

- 2.Gómez-Oro C, Latorre MC, Arribas-Poza P, et al. Progesterone promotes CXCl2-dependent vaginal neutrophil killing by activating cervical resident macrophage–neutrophil crosstalk. JCI Insight. Published online October 22, 2024. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.177899

- 3.Wieser F, Hosmann J, Tschugguel W, Czerwenka K, Sedivy R, Huber JC. Progesterone increases the number of Langerhans cells in human vaginal epithelium. Fertility and Sterility. Published online June 2001:1234-1235. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01796-4

- 4.Hughes SM, Levy CN, Katz R, et al. Changes in concentrations of cervicovaginal immune mediators across the menstrual cycle: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMC Med. Published online October 5, 2022. doi:10.1186/s12916-022-02532-9

- 5.Teal S, Edelman A. Contraception Selection, Effectiveness, and Adverse Effects. JAMA. Published online December 28, 2021:2507. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.21392

- 6.Smith-McCune K, Thomas R, Averbach S, et al. Differential Effects of the Hormonal and Copper Intrauterine Device on the Endometrial Transcriptome. Sci Rep. Published online April 23, 2020. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-63798-8

- 7.Prior JC. Perimenopause: The Complex Endocrinology of the Menopausal Transition. Endocrine Reviews. Published online August 1, 1998:397-428. doi:10.1210/edrv.19.4.0341

- 8.Süss H, Willi J, Grub J, Ehlert U. Estradiol and progesterone as resilience markers? – Findings from the Swiss Perimenopause Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. Published online May 2021:105177. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105177

- 9.Joffe H, de Wit A, Coborn J, et al. Impact of Estradiol Variability and Progesterone on Mood in Perimenopausal Women With Depressive Symptoms. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. Published online November 6, 2019:e642-e650. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgz181

- 10.Hee J, MacNaughton J, Bangah M, Burger HG. Perimenopausal patterns of gonadotrophins, immunoreactive inhibin, oestradiol and progesterone. Maturitas. Published online December 1993:9-20. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(93)90026-e

- 11.Gompel A. Progesterone, progestins and the endometrium in perimenopause and in menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric. Published online March 27, 2018:321-325. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1446932

- 12.Prior J. Progesterone for Symptomatic Perimenopause Treatment – Progesterone politics, physiology and potential for perimenopause. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2011;3(2):109-120. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24753856